Health Mother, Healthy Child

Northwestern Medicine goes the extra mile to support people with high-risk pregnancies.

by Martha O’Connell

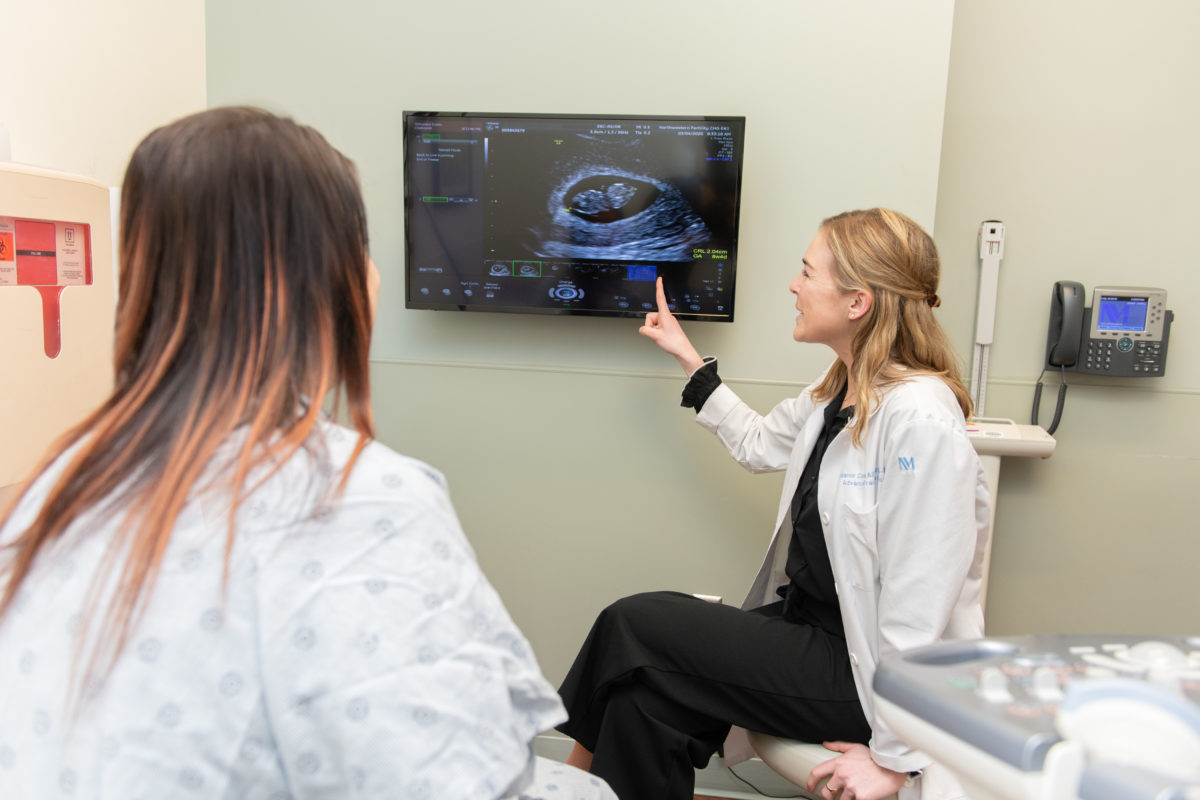

Shaina Herring is no stranger to dramatic births. Her first child arrived at 32 weeks. Her second came at 34 weeks — after she’d gone into labor at 27 weeks and stayed at the hospital until he was born. With baby number three on the way, she was seeking as much peace of mind as she could get.

“I was drawn to Northwestern’s Maternal-Fetal Medicine program because I knew I would need monitoring with this pregnancy,” she says. “I wanted to be able to assure my kids that everything would be OK.”

Herring came to the right place. From her earliest visits, she received cervical ultrasounds, weekly progesterone shots, and her gestational diabetes was promptly identified and addressed.

“A newborn cannot be healthy without a healthy mom,” says Janelle Bolden, MD, chief of the division of Maternal-Fetal Medicine (MFM) at Northwestern Memorial Hospital and of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at Feinberg.

From mood disorders to HIV/AIDS to birth defects and other challenges, the division is prepared to treat anything that comes up in the critical perinatal period. But Bolden stresses that care is not always about treatment.

Specialists also provide counseling so patients can make informed decisions about health management, reproductive choices, and fetal interventions. “One might think that MFM’s role lasts nine months, plus the two months following delivery, but it’s just the opposite,” says Bolden, who is also an associate professor of Obstetrics and Gynecology and of Medical Education at Feinberg.

“When we care for expectant mothers, we are not just talking about the next couple of weeks or months. We are talking about 10 to 20 years down the line: when things like weight management, mental healthcare, and exercise will continue to make a major difference in overall health.”

At Northwestern Medicine, this holistic philosophy is manifested through a range of programs designed to cater to each pregnant person’s individual needs, particularly those who live in neighborhoods affected by violence, food deserts, and other stress-inducing life circumstances that pose health risks to both mother and child.

Battling Diabetes as a Team

The obesity epidemic in the U.S. has become the diabesity epidemic, resulting in an enormous need for specialized care for women who either enter pregnancy with diabetes or develop gestational diabetes (putting them at higher risk for Type 2 diabetes later in life). In the last two decades, MFM has seen the number of individuals in its Diabetes and Pregnancy Program double.

Achieving glycemic control during pregnancy is a constant challenge that requires close monitoring of medications, patient-reported blood glucose numbers, and adherence to healthy eating and regular exercise. Lack of access to nutritious foods and medications make pregnant people with diabetes especially vulnerable to poor outcomes. For patients like Herring, who work nights and don’t always have access to healthy foods, care plans and routines often need to be adapted.

“Our goal is to meet patients where they are. Thinking through what barriers they have to overcome in order to adhere to their diets, pick up their prescription, and then take that prescription multiple times a day is a big part of the work we do,” says Lynn Yee, MD, ’08 MD, ’15 GME, a leader of MFM’s diabetes program and assistant professor of Obstetrics and Gynecology at Feinberg.

With the significant numbers of pregnant individuals who need care, teaching front-line obstetricians to manage gestational diabetes on their own has become essential to MFM’s approach. In addition, the Prentice Ambulatory Care Clinic, serving low-income patients, provides comprehensive care for pregnancy patients with diabetes. MFM physicians have also incorporated technology as an effective method for monitoring their patients more accurately. Individuals with Type 1 diabetes often receive wearable glucose monitors that measure glucose levels throughout the day and allowing information about their glucose levels to be easily shared with the medical team.

Yee is taking technology a step further with an app her lab designed to support and motivate pregnant individuals with gestational or Type 2 diabetes. The app, SweetMama, is the first health app to manage diabetes among low-income, socially disadvantaged individuals. Patients receive a customized curriculum according to their gestational age, including health education and logistical help to find stores and food pantries for healthy foods, safe places to exercise, sources to obtain medications, and even nutritional recipes. The app also helps them set and achieve goals such as walking 20 minutes a day, or logging glucose numbers before every clinic visit.

SweetMama received positive reviews from patients during pilot studies, and Yee is continuing to refine the app in the hopes of widespread distribution.

When we care for expectant mothers, we are not just talking about the next couple of weeks or months. We are talking about 10 or 20 years down the line.

Janelle Bolden, MD

Supporting Women Affected by HIV

Now celebrating its 30th year, the Women’s Infectious Disease Program at Northwestern Medicine has come a long way since the days when, tragically, many women with HIV/AIDS had a 25 to 30 percent chance of passing on the virus to their baby and would probably not live to see their child graduate from high school.

Back in 1990, before there were effective therapies to keep people alive or knowledge about how HIV was transmitted to babies, Patricia Garcia, MD, MPH, ’91 GME, then a fellow, along with her co-fellow, the late Michele Till, MD, ’92 GME, began to care for pregnant women with HIV. Through the generous support of Northwestern Memorial Woman’s Board, they slowly garnered the resources necessary to develop a clinic with interdisciplinary care and participated in research that eventually resulted in the ability to prevent perinatal HIV transmission.

Decades later, the clinic staff has helped to deliver hundreds of babies free of HIV and keep their mothers healthy. “It takes a village and we have an amazing one that includes our incredible clinic nurse, Brianne Condron, RNC-MNN, and dedicated social worker Siret Beraki, LMSW, along with MFM and infectious disease physicians, pharmacists, and a psychologist. This is what it takes to keep women connected to care and help them to overcome the challenges of stigma, medication adherence, and controlling the virus,” says Garcia, who is a specialist in MFM and associate dean for curriculum at Feinberg.

This is about much more than keeping women alive. It is about our role in advancing research, training the next generation of HIV care providers, and advocating for the resources needed to value and respect people living with HIV.

PATRICIA GARCIA, MD, MPH, ’91 GME

“Our obligation is to never forget the care and respect that our patients need and deserve; to never take our eye off the problem because, once we do, HIV will come roaring back and so will perinatal transmission,” she adds.

Even while HIV has become a potentially controllable disease through an arsenal of effective drugs, as far as Garcia is concerned, that is only half the mission. “This is about much more than keeping women alive,” she says. “It is about our role in advancing research, training the next generation of HIV care providers, and advocating for the resources needed to value and respect people living with HIV.”

Expanding Access to Mental Health Care

Depression, which often has roots before pregnancy begins, is one of the most common mental conditions encountered during pregnancy, yet many obstetricians feel unqualified to treat it. That is why, in 2017, MFM specialist Emily Miller, MD, MPH, ’14 GME, partnered with colleagues in psychiatry to launch the Collaborative Care

Model for Perinatal Depression Support Services (COMPASS). In addition to depression, COMPASS treats women with all other mental health conditions. About 70 new pregnant or postpartum people enroll in the program every month, some of whom participate in the division’s robust clinical trials. To expand the reach of COMPASS, Miller spends time meeting with obstetric and mental health clinicians across the country to educate them on the collaborative care model. Her goal is to partner with and educate obstetric clinicians outside the Northwestern Medicine network — preparing as many practitioners as possible to confidently care for pregnant and postpartum people with mental health conditions.

“We are able to care for a large number of individuals with perinatal mental health conditions because we know we can empower OBs and midwives to manage standard perinatal depression and anxiety with the support of the collaborative care team,” Miller says. She got the idea for COMPASS after seeing how effective collaborative care models have improved mental health outcomes in internal medicine settings and wanted to adapt this approach to the prenatal and postpartum context.

The initiative has been supported by faculty in the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, as well as the Asher Center for the Study and Treatment of Depressive Disorders, which is led by Katherine Wisner, MD, the Norman and Helen Asher Professor of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences and Obstetrics and Gynecology.

Pregnant and postpartum people who are patients of Northwestern Medicine are supported through either psychotherapy and/or pharmacological treatment. Importantly, treatment does not end after pregnancy.

“This is something that is relatively novel in obstetrics — we do not start treatment and send people off without follow-up postpartum. We partner with them up to a full year postpartum,” says Miller, who is also an assistant professor of Obstetrics and Gynecology and of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences at Feinberg.

COMPASS addresses holistic care for all individuals. Accomplishing a rare feat, the program brings an obstetrician, mental health experts, and social workers together in the same room to ensure that patients’ obstetric, mental health, and social needs are answered.

“Having two social workers at the helm of this program really makes us responsive to the social determinants of health. We are lucky. Irrespective of insurance, we are committed to providing care to all our pregnant and postpartum patients with mental health concerns,” Miller says.

Preserving the Birth Experience During a Pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic forced MFM to rapidly put extensive safety measures in place, so that Prentice Women’s Hospital, where 2,000 infants are delivered each year, could reassure people giving birth that they and their newborns would be safe.

The MFM team made this possible by designing a space on the ninth floor for pregnant people infected with SARS-CoV-2. The space was outfitted with negative air pressure, optimized infection prevention designs to mitigate healthcare workers’ exposure, and a designated staff. The team conducted emergency simulations, and learned how to transport patients with SARS-CoV-2, how to test infants for the virus, how to approach breastfeeding, and more.

“This may all sound simple on the surface, but we have been drinking from a firehose of scientific information that changes monthly about best practices,” says Miller, who was at the helm of averting a crisis.

Then, there is the monumental task of preserving a momentous occasion for new parents — that moment when they first have the chance to hold their baby — without letting COVID-19 steal it away.

As mounting evidence has shown, newborn separation is no longer recommended and other infection mitigation strategies can keep newborns safe. But in the early days of the pandemic, Miller recalls that members of the team sat at the bedside to comfort pregnant people to try to blunt the trauma of not having the normal contact with the newborn.

“I work with a brilliant and empathic group of obstetric clinicians, and Northwestern Medicine has been a real leader in understanding the implications of this virus on pregnancy and childbirth,” she says.

As for Herring, the mom who turned to Prentice for her high-risk care, she made it to 38 weeks during the height of the Omicron surge when daughter Orly was born. The baby is doing well, and so is Herring. The MFM team will make sure she does for years to come.