Home / Alumni News / Alumni Profile:Health is More Than Healthcare

Alumni Profile:

Health is More Than Healthcare

John Lumpkin Tackles Health From All Sides

by BRIDGET M. KUEHN | illustration BY JACQUI OAKLEY

The average American spends just 60 minutes a year receiving healthcare, says John Lumpkin, ’73 BMS, ’74 MD — not enough time to tackle the harmful effects of health inequities or resolve the chronic diseases that too often result from them.

“Health is more than healthcare,” said Lumpkin, the recipient of the 2020 Feinberg Distinguished Medical Alumnus Award. “Health happens where people live, where they work, where they recreate, where their life is spent — in their communities. We can work with those communities to help them be places that encourage health as opposed to put up barriers to health.”

In his dual roles as president of the Blue Cross and Blue Shield (BCBS) of North Carolina Foundation and vice president, Drivers of Health for Blue Cross and Blue Shield of North Carolina, Lumpkin is working on innovative programs to help overcome inequities that can lead to poor health. For example, the health insurance company works with food banks and a nonprofit called Benefits Data Trust to help members who are food insecure sign up for the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP). They are also piloting a program with Reinvestment Partners in Durham and Food Lion, a large grocery chain, called SuperSNAP that will provide member SNAP recipients with an additional $40 a month to purchase fresh produce.

“Our vision is to help make North Carolina one of the healthiest states in the nation in a generation,” says Lumpkin.

A Bigger Impact

A tragedy — the murder of family friend and civil rights activist Fred Hampton in 1969 by police as he slept — set Lumpkin on his path to be coming a physician. At the time, he was a freshman studying biophysics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, but the loss of Hampton made him want to have a bigger impact. He transferred into Northwestern’s six-year Honors Program in Medical Education (HPME) in 1970.

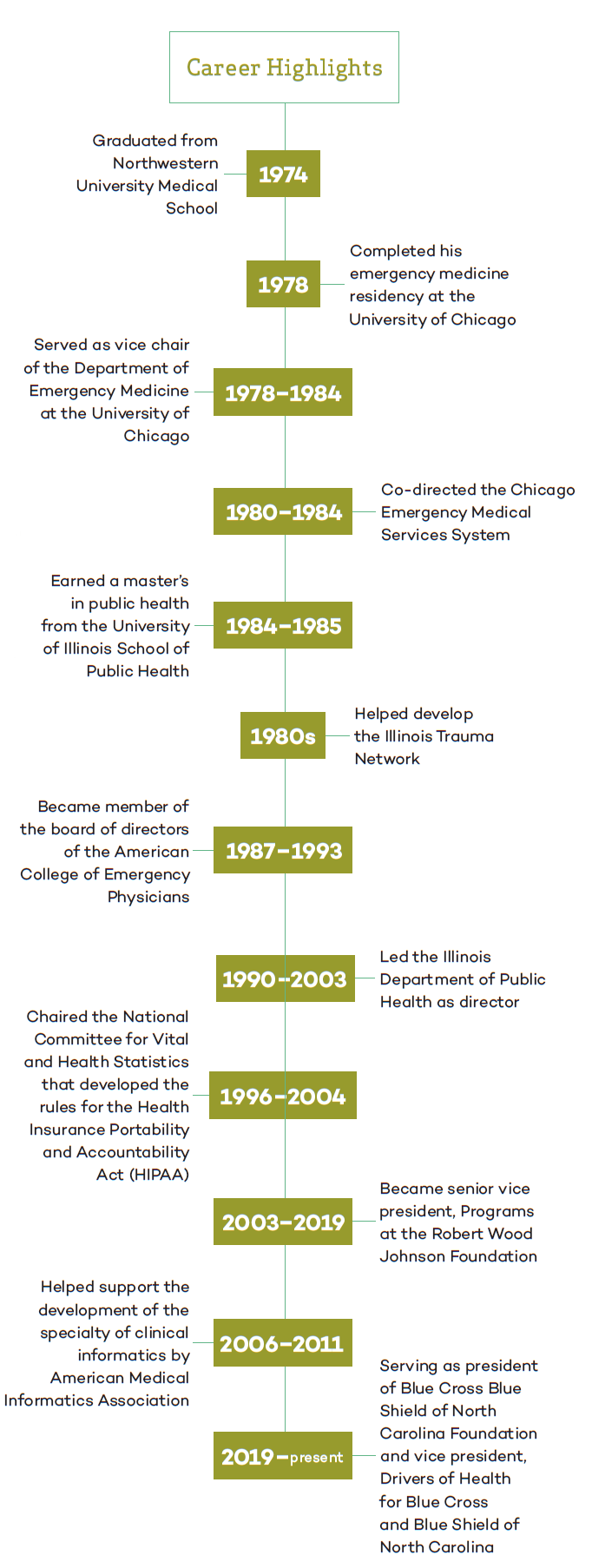

His advisor Jeremiah Stamler, MD, professor emeritus of Preventive Medicine in the Division of Epidemiology, who was very interested in social and preventive medicine, helped Lumpkin tailor his education to pursue a career in the nascent specialty of emergency medicine. Lumpkin was the first African American and one of the first 200 residents to train in emergency medicine. During his tenure on the board of directors of the College of Emergency Physicians, he helped conceptualize the current model for emergency residency. Working in an emergency department inspired him to earn a master’s in public health at the University of Illinois.

“If you work in the emergency department, you see how the healthcare system fails because when it fails, by and large, people end up in the emergency department,” he says.

In 1990, Lumpkin was appointed the first African American director of the Illinois Department of Public Health. During his tenure, he served under three governors and helped boost the department’s preparedness for emergencies and disasters in the wake of September 11, 2001. In the months that followed, the department ran thousands of tests on samples suspected of being anthrax. Lumpkin says he was proud of the legacy of preparedness he left behind and the fact that he helped open the door for others. In fact, every director since his tenure has been a person of color, including the current director Ngozi Ezike, MD, who is leading Illinois’s response to the pandemic.

“I’ve been fortunate enough to have been a trailblazer,” says Lumpkin. “I like to think that I did a good enough job as director that they saw [having a person of color in the lead]as being something important.”

Health Equity Focus

After leaving the Illinois Department of Public Health, Lumpkin joined the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation as senior vice president, Programs. While there, he led a nationwide campaign to reduce childhood obesity.

The opportunity to leverage both the tools of a large not-for-profit insurer serving 3.8 million North Carolinians and a philanthropy drew him back to state-level work. Now, he’s using those tools, including BCBS of North Carolina’s massive data set and value-based payment systems, to help tackle the historical and structural factors that contribute to health inequity in North Carolina.

“In a number of communities across North Carolina, there are structural barriers that are a result of historical disinvestment that has occurred as a result of structural racism that we have within our society and within the state of North Carolina,” he says.

That work has become even more critical as the pandemic exacerbates existing disparities.

“The fact is that this epidemic has disproportionately affected African Americans and Hispanics, especially in the state of North Carolina,” he says. “Our programs have been modified to address that.”

The foundation has long emphasized quality early-childhood education, which is crucial for life-long health and opportunity. But, in the wake of the pandemic, it has shifted its focus to the brewing childcare crisis in the state, where an estimated half of childcare centers are in danger of closing down as a result of a months-long shutdown, Lumpkin explains. To help these small, often women-run, businesses reopen, the foundation is partnering with nonprofit organizations that can provide financial guidance.

“It’s that kind of technical assistance that doesn’t normally exist that could be the difference between opening and shutting down forever,” he says.

Lumpkin credits Northwestern for allowing him to customize his education and giving him the foundation necessary to become a leader at the state and national level.

“It’s the excellence in clinical grounding, which, to this day, I appreciate, because I understand how medicine works,” he says. “I understand how the healthcare system works.”