by EMILY AYSHFORD

The new Starzl Academy supports the next generation of physician-scientists.

As an undergraduate getting his first experience in a research lab, Sam Weinberg, MD, PhD, found what many others before him had found: that scientific research was the perfect place to ask questions and figure out creative ways to answer them.

But when he attended professors’ presentations, he often found their research to be obscure and unattached to real problems. “I wanted to do research on actual problems that affect people,” he says. “For me, medicine seemed like the ideal place to do that.”

That led him on what is a rare trajectory: that of a physician-scientist. In this role, physicians meld two careers into one, working on patient-centered problems in the clinic while conducting research in the lab that could lead to the next new therapy or diagnosis. Physician scientists are often at the forefront of finding solutions for patients’ needs — many budding physician-scientists at Northwestern have already published studies in several high-impact journals — but they must also find the stamina to succeed in what are essentially two separate paths.

That’s why Feinberg recently created the Starzl Academy, an umbrella program for the school’s many formal and informal Physician-Scientist Training Programs. The new academy provides tools and resources for budding physician-scientists, helping them secure mentorships, succeed in writing grants, and create a multi-level support network.

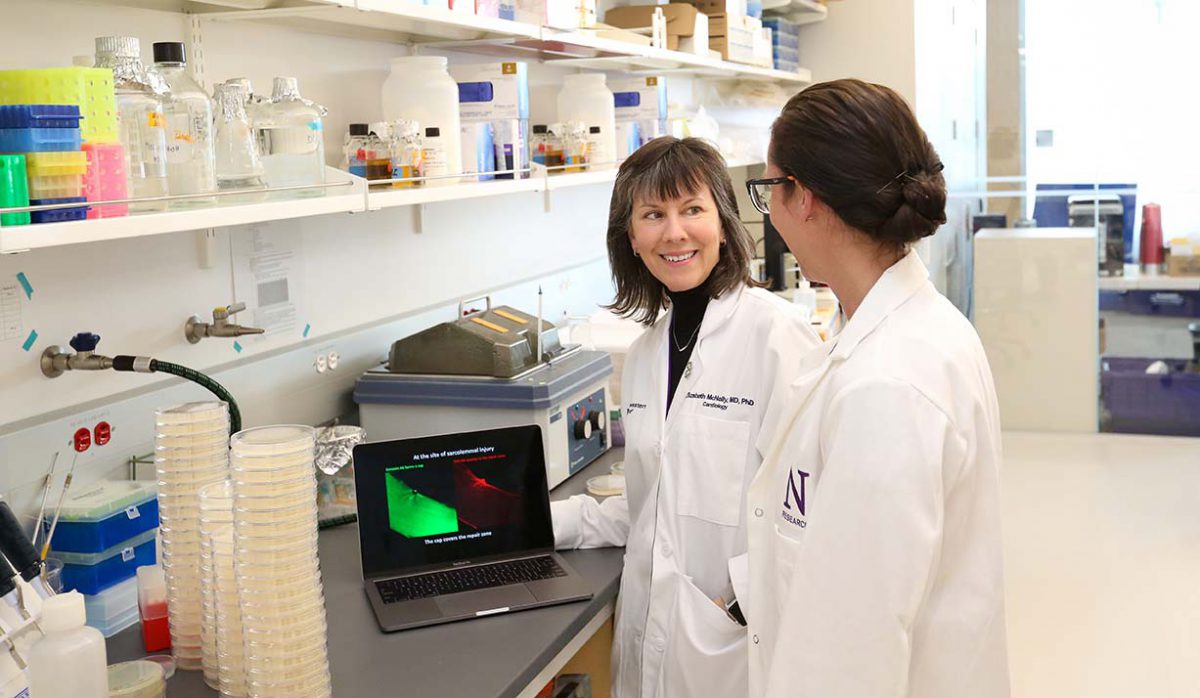

“It’s increasingly challenging to blend these two careers together,” says Elizabeth McNally, MD, PhD, professor of Medicine in the Division of Cardiology and of Biochemistry and Molecular Genetic, who directs the academy. “Physician-scientists make up a small percentage of the workforce, but they are essential for advancing human health. When you’re forging this unique path, you really need the right resources to succeed.”

Becoming okay with failure

For Weinberg, that unique path led him to pathology. After completing his MD and PhD at Northwestern, he became a resident and research fellow, allowing him to conduct testing on patient samples while also exploring research questions in a laboratory setting. He studies how changes in a person’s metabolic environment can affect their immune system. In the lab, he has examined regulatory T cells, which suppress the immune system and which can cause autoimmunity if their numbers are too few. His work on suppressing the mitochondrial function in these cells garnered him a first-author publication in Nature.

“We ultimately want to tease out the pathways and regulation of immune cells to help fight autoimmunity or get the immune system to attack tumors,” he says.

That kind of success is what sets apart physician-scientist trainees at Northwestern, says Peng Ji, MD, PhD, associate professor of Pathology. “Sam is an outstanding physician-scientist trainee with a bright future,” Ji says. “He will be a role model for our future trainees.”

But that doesn’t mean Weinberg’s research path has always been smooth. “It’s difficult, frustrating, and time-consuming,” he says. “When you finish medical school and get into the lab, you’re at the bottom of the totem pole, and it seems like nothing is working. You have to learn to be okay with failure, with the hope that one day you’ll affect people’s lives.”

A perfect marriage of care and research

Aspiring physician-scientists have to be constantly curious and innovative about problems in the clinic. For Luisa Morales-Nebreda, MD, that means working to understand the different ways that acute lung injury can present itself — and be treated. She started working on the problem in her native Venezuela, trying to understand how scorpion venom induces lung injury.

As a physician-scientist trainee, she is now studying the mechanisms behind influenza, pulmonary fibrosis, and, more recently, COVID-19.

“We want to understand how people can recover from lung injuries,” she says. “If we can understand the cellular or molecular mechanisms that underpin what’s happening in the lungs, we can hopefully understand how to enhance recovery.” Her research involves systematically taking fluid samples from ICU patients and analyzing their content, and has led to journal publications in the Journal of Experimental Medicine, Journal of Clinical Investigation, and Cell Metabolism.

Being a physician-scientist is the “perfect marriage between delivering care to patients and working to ask the questions on how care can be improved,” she says. “For many diseases, like pulmonary fibrosis, we don’t have much to provide to patients. That’s very frustrating. If we can find new methods or therapeutics that could help patients — that’s a very valuable goal for me.”

Morales-Nebreda credits her success in part to several mentors, including Benjamin Singer, MD, assistant professor of Medicine in the Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care and of Biochemistry and Genetics. “Having a mentor is the most important part of success as a physician-scientist,” she says. “They are essential to giving you guidance and keeping you on track.”

“It has been a great pleasure to mentor Luisa,” Singer says. “She is an all-star trainee, excelling in each domain of our tripartite mission of clinically-relevant discovery, exceptional patient care, and education of the next generation.”

From bedside to bench, and back again

For Elnur Babayev, MD, having mentors who are both physicians and scientists has been critical to asking key research questions, like how aging affects reproduction. As a clinical fellow in reproductive endocrinology and infertility, Babayev has studied what happens to ovaries and the cumulus cells around eggs as women age. His work has garnered him publications in journals like Aging Cell and Fertility and Sterility.

Sometimes you can feel like you’re on your own. We want to help physician-scientists understand grant opportunities and understand all the resources available to help them.

Elizabeth McNally, MD, PhD

Now, he is working to understand the quality of eggs in adolescent patients who preserve their eggs before undergoing chemotherapy or gender transitioning hormonal treatments, which can affect fertility. “We want to know — are these eggs of the same quality as adult eggs?” he says. “There is not a lot of research in this area. I’m fascinated by how aging affects reproduction, and projects like this are an opportunity for me to be involved in clinical care and treat infertility patients while also thinking about big problems in the field. It’s a bed-to-bench loop to try and see what problems we can solve.”

That’s the kind of approach that makes physician-scientists so successful, says Eve Feinberg, MD, associate professor of Obstetrics and Gynecology. “Elnur is one of the brightest minds I have encountered,” she says. “He is inquisitive and will not stop researching until he is able to find answers.”

Making a difference in patients’ lives

Encouraging bright minds like this is the goal of the Starzl Academy, says McNally. As a physician-scientist herself who studies the genetics of cardiovascular and neuromuscular disorders, she gets “pulled in a lot of different directions.”

“Sometimes you can feel like you’re on your own,” she says. “We want to help physician-scientists understand grant opportunities and understand all the resources available to help them.”

Even if it sometimes feels like double the work, a career as a physician-scientist can also be doubly rewarding: McNally, who is the Elizabeth J. Ward Professor of Genetic Medicine, is now seeing the field embrace genetic therapies that can provide treatment to previously untreatable diseases. “That’s taking your training and making a difference in lives,” she says.