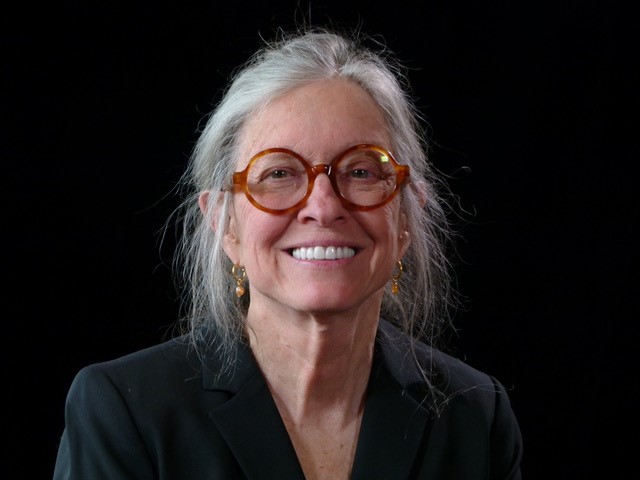

Home / Alumni News / Accepting the Difficult Gifts of a Cancer Diagnosis

Accepting the Difficult Gifts of a Cancer Diagnosis

By Courtney Burnett, ’17 MD

As a primary care and hospital medicine provider in St. Paul, Minnesota, I, like many of my fellow Feinberg alumni, have spent the last year working on the frontlines of the COVID-19 pandemic. But, unlike (hopefully) many of you, I’ve also spent the last year battling brain cancer.

During my third year of my internal medicine residency at the University of Minnesota, I spent a month studying in Thailand. While there, I developed strange symptoms, including tingling in my left hand and difficulty swallowing, and ended up diagnosing myself with a brain tumor. Unfortunately, this turned out to be a malignant brain cancer, requiring two brain surgeries, chemotherapy, and radiation.

Fortunately, I’m still here to tell you my story. I was extremely lucky that cancer did not impact my ability to practice medicine. Instead, I’ve found that my experience as a patient — particularly in those early days at a hospital in Thailand — became one of my most valuable medical lessons.

The evening after my initial brain scan showed a brain tumor, I was admitted for urgent evaluation and treatment for seizures and brain swelling. Although the medical care system works differently in Thailand than in America, many of the basic logistical aspects were familiar to me. I knew that the physician would order initial labs and vital sign checks, so I was prepared when the lab technician came into my room, stuck an IV in me, and took a few vials of blood without saying a word. I was also mentally prepared to be woken up from sleep every few hours for vital signs, routine monitoring of my heart rate, blood pressure, and oxygen levels. Every time a familiar activity happened, I felt grateful. OK, I know what this is. I can feel the blood pressure cuff squeezing my arm. I can read my blood pressure measurement; I know this number is OK. When an IV pole was wheeled into my room and fluids were hung next to me, I thought, OK, this is a familiar intravenous fluid. I know why the physician ordered this and I know what effects it will have on me. None of this was explained to me as it was happening.

I decided then that when I was back at work, I would try to spend a few extra minutes with my own patients and provide them with knowledge to feel safe, respected, and understood, rather than afraid and confused.

As a physician, I often make the decision to order labs, place IV lines, start fluids, and do vital sign checks without informing my patients of these decisions. I always inform my patients of critical changes in their treatment plans or test results; however, routine tasks such as those above are as commonplace in medicine as sending an email would be in the corporate world. Physicians do not always remember that for patients, an email feels very different than a blood draw.

I absolutely cannot fathom how terrifying it would be to be a patient, let alone a patient in a foreign country, lying alone in a hospital room undergoing the above procedures without knowing why these things happen, when they happen, or what the results mean. The only reason I felt comfortable in this situation was that it is my day-to-day job.

Being a patient is terrifying. Autonomy is gone. You find yourself with a million unanswered questions, and you spend hours waiting for a physician you just met to tell you the worst news of your life. After this hospital admission, I decided then that when I was back at work, I would try to spend a few extra minutes with my own patients and provide them with knowledge to feel safe, respected, and understood, rather than afraid and confused.

In the end, one of the greatest difficult gifts of my cancer diagnosis and treatment was actually my experience being a patient. Cancer has taught me more about living, mortality, health, wellness, and patient care than any textbook ever could.

This piece was adapted from Burnett’s memoir Difficult Gifts: A Physician’s Journey to Heal Body and Mind, available at www.elephantlotusbraintumor.com, Amazon, Barnes and Noble, or at your local bookstore.