by CHERYL SOOHOO | photography by KIM BECKER

Minimally-invasive innovations achieve life-changing outcomes sooner.

No one wants major “open” surgery when a minor or minimally-invasive procedure could yield as good, if not better results. Most, if not all, patients would prefer to have a choice of the most effective treatment options with less pain, lower risk of infection, little scarring, shorter or no hospital stay, and faster recovery.

Not surprisingly, striving to meet these expectations and achieve better outcomes has accelerated innovations in interventional medicine in ways that would have been unimaginable in the not-so-distant past. Today, many areas of the body can be accessed through less than one-inch incisions or no incisions at all to treat ailments ranging from a faulty heart valve to brain aneurysms.

At the forefront of these advancements, Northwestern Medicine has long promoted a culture of innovation tempered by discipline and clinical-research checks and balances.

“The strong entrepreneurial spirit cultivated here and willingness to creatively use technology to improve care has allowed us to be pioneers,” says Howard Chrisman, MD, MBA, interim chair of the Department of Surgery and professor of Radiology and Surgery. “It is what drives our talented physicians to develop and perform these advanced procedures so that patients leave us healthier than when they came to us.”

To that end, Northwestern physicians in myriad specialties are breaking new ground every day by perfecting novel interventional techniques.

Not Easy to Digest

Eat. Sleep. Study. Repeat. As a grad student at the University of Illinois in Urbana-Champaign, Gabriela Vargas needed to follow these daily rituals if she had any hopes of completing her PhD degree in mathematics education. Yet after undergoing an esophagectomy — surgical removal of the esophagus — in 2016 to treat achalasia, a disorder of low to zero mobility of the esophagus, Vargas, a foodie with an adventurous palate, steadily began to find food to be the enemy. Eating made her nauseous, her stomach felt full after a few bites, and terrible heartburn kept her from sleeping.

“It was an endless cycle of throwing up after meals, being awaken by acid reflux, and having little energy to function at school,” says Vargas. “I often had to negotiate with myself and make the decision to eat even though I knew I would get sick.”

In July 2018, Vargas’ symptoms ramped up after the repair of a diaphragmatic hernia related to her esophagectomy. During the past three years, her nausea, bloating, and feeling of fullness have led to a total weight loss of 60 pounds. This April, further diagnostic testing revealed the root cause of her gastrointestinal distress: gastroparesis, a complex condition that prevented her stomach from properly emptying. The term gastroparesis literally translates to partial paralysis (paresis) of the stomach (gastro), and the disease may occur for many reasons, from diabetes to foregut surgery. Lack of stomach motility can also result from spasms of the pyloric sphincter, a smooth band of muscle at the end of the stomach that serves as the gateway to the rest of the digestive tract.

The strong entrepreneurial spirit cultivated here and willingness to creatively use technology to improve care has allowed us to be pioneers

Howard Chrisman, MD, MBA

When the pyloric sphincter relaxes, it allows food to pass into the small intestine. When it doesn’t open and close as it should, food lingers in the stomach for far too long.

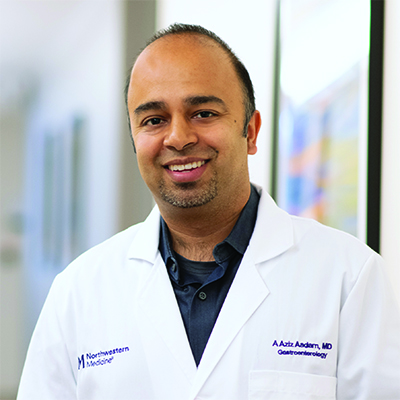

“Gastroparesis can be very debilitating for patients,” says Aziz Aadam, MD, assistant professor of Medicine in the Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology. “While diet changes and some medications can help, there aren’t many good long-term medical options especially for patients with refractory disease.”

Until now.

A Novel GI Procedure

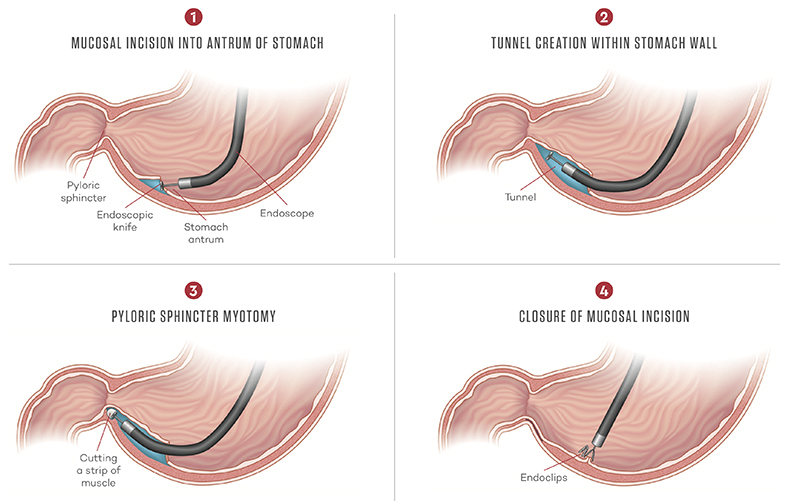

A little over two years ago, Aadam, an interventional gastroenterologist and director of Northwestern’s Developmental Endoscopy Program, began performing a novel minimally-invasive procedure known as G-POEM (gastric per-oral endoscopic pyloromyotomy). Used to treat gastroparesis, it involves passing a standard endoscope — a flexible tube with a camera on the end — through the mouth and down the esophagus. Once he reaches the bottom of the stomach, Aadam deploys the one-centimeter endoscope through a small internal incision to create a tunnel in the middle layers of the stomach to reach the pylorus sphincter muscle. He then cuts out a strip of the muscle to prevent further spasms, allowing the stomach to empty and the digestive tract to do its job.

We have transitioned from the diagnostic era to the therapeutic era of endoscopy.

Aziz Aadam, MD

Performed on an outpatient basis, G-POEM has the potential to replace traditional open surgery and the now more commonly used laparoscopic approach, which can have drawbacks such as pain at the external incision site. With G-POEM, patients have minimal to no pain and can eat right away. So far, of the some 40 patients who have participated in the G-POEM clinical study at Northwestern, 75 percent have shown improvement with 50 percent able to normalize their gastric-emptying study.

This test uses X-ray technology to objectively measure the time it takes for food to move out of the stomach. Within three weeks of her G-POEM procedure this past July, Vargas says she began to enjoy her relationship with food again. “As long as I eat smaller amounts and several meals throughout the day, I am fine.”

Aadam works with a multidisciplinary G-POEM team, which includes Darren Brenner, MD, who specializes in gastrointestinal motility disorders and pelvic floor disorders, dieticians, and, uniquely, a clinical health psychologist, Kate Tomasino PhD. Very much a “brain-gut” disease, emotional states such as depression can exacerbate symptoms, according to Aadam. He has high hopes for the potential of this innovative procedure that he learned how to perform in Japan at the National Cancer Center in Tokyo. In 2015, he spent a month honing his skills in endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) used to endoscopically remove early GI cancers. He trained under the mentorship of the foremost expert in colorectal ESD, Yutaka Saito, MD, PhD. G-POEM is a novel extension of ESD.

“We have transitioned from the diagnostic era to the therapeutic era of endoscopy,” says Aadam. “Now we are making minimally-invasive internal incisions that heal quickly. This really is an exciting new era that puts us at the crossroads between medical and surgical intervention.”

vice chair of Image-Guided Therapy and chief of Vascular Interventional Radiology in the Department of Radiology

GAME CHANGER FOR IMPROVING MEN’S HEALTH

Treatment options have been limited for the 15 to 20 million men in the United States with enlarged prostates or benign prostate hyperplasia (BPH) — a common disease in men over 50 — and the urinary issues it causes.

A growing prostate puts pressure on the bladder, causing difficulties urinating from increased frequency to problems fully emptying the bladder. TURP (transurethral resection of the prostate) is the current gold standard for improving the often life-altering symptoms of BPH, which can have men going to the bathroom as many as 15 times a night. The risks of this procedure include erectile dysfunction, incontinence, and recurring urinary tract infections — serious side effects that affect quality of life for men as they age.

Enter prostatic artery embolization (PAE), a cutting-edge minimally invasive procedure that shrinks the prostate by cutting off its blood supply via the use of very small microspheres or beads. Leading the way, a multidisciplinary team of Northwestern Medicine interventional radiologists and urologists have been evaluating the innovative procedure in clinical trials.

“One of the most appealing aspects of PAE is that there is no risk of sexual dysfunction,” says Riad Salem, MD, vice chair for Image-Guided Therapy and chief of the Division of Vascular Interventional Radiology in the Department of Radiology. “With this minimally-invasive outpatient procedure, patients experience very little pain, go home the same day, and can soon get back to normal activities.”

PAE involves threading a catheter up through the femoral artery in the groin to the prostate. Then the interventional radiology team injects the tiny beads so they block off the arteries feeding the prostate. The image-guided procedure effectively reduces the size of prostate, so it no longer presses on the bladder. The Northwestern team of Salem, along with Matthias Hofer, MD, PhD, and assistant professor of Urology, and Samdeep Mouli, MD, assistant professor of Radiology, has found PAE works best on very large prostate glands (> 80cc) with the necessary vascular architecture. “The arteries feeding larger glands are a better receptacle for the microspheres,” says Salem.

As PAE becomes more widely known and accepted, many patients have sought it out, according to Salem.

“We have had good results with PAE that suggest that it should become one of the standards of care for BPH,” says Salem. “It is a very attractive first treatment for men with enlarged prostates.”