Home / Alumni News / Advancing Health and Science Through Informatics

Advancing Health and Science Through Informatics

by Bridget M. Kuehn

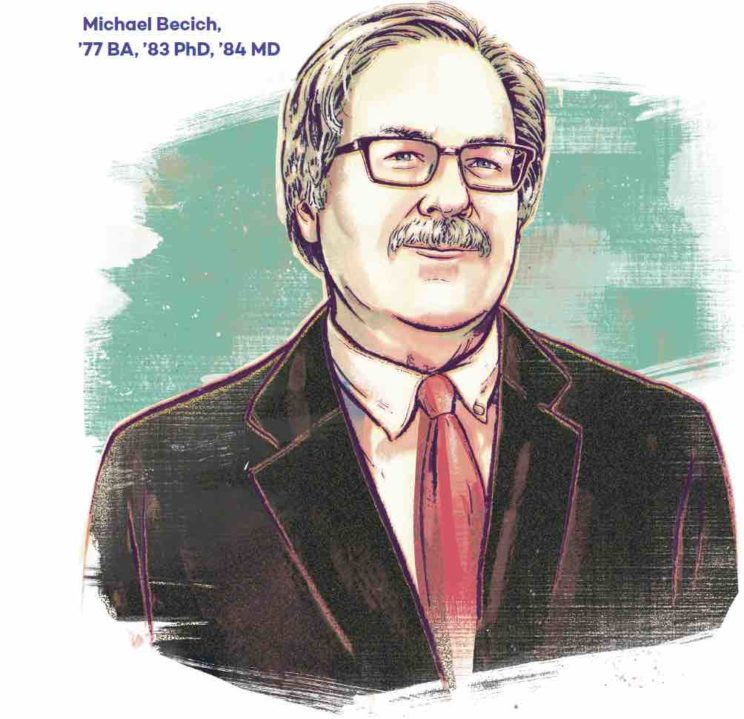

As pathologists increasingly use machine-learning technologies to analyze digitized patient slides, they face a challenge: They have difficulty trusting computer-generated results. Michael Becich, ’77 BA, ’83 PhD, ’84 MD, aims to solve this concern through a new technology called “explainable artificial intelligence.”

Becich, chairman and Distinguished University Professor in the Department of Biomedical Informatics at the University of Pittsburgh, and his colleagues in Pathology have launched a start-up company called SpIntellx and created a tool called HistoMapr. This tool presents its findings — and how it reached them — to clinicians, who can then decide what to do based on the information.

“The goal isn’t to tell the computer to make the diagnosis, the goal is to give the pathologist a cockpit of better-informed imaging tools that help guide them to the most correct answer to ensure safer and efficient care,” says Becich, who is also the University of Pittsburgh’s associate vice-chancellor for Informatics in the Health Sciences.

The work is the latest chapter in a career that has taken Becich from a cancer pathologist to a leader in the emerging field of biomedical informatics. Along the way, he has helped launch two leading academic initiatives and a department, trained scores of young people, and launched multiple start-ups.

Bringing informatics to pathology

Although he never trained in informatics, Becich’s use of computers to manage tumor biology imaging data during his graduate studies in cancer pathology at Northwestern caught his colleagues’ attention. During his residency, fellowship, and first faculty position at Washington University in St. Louis in the 1980s, he became a “go-to person” for computer-driven pathology data management. In 1991, he was hired by the University of Pittsburgh, where he helped create its first division of pathology informatics — only the second such division in the country. He also helped, in 1996, to create and run the Advancing Pathology Informatics Imaging in the Internet annual meeting (which is now called the Pathology Informatics Summit). He also helped found the Association for Pathology Informatics (2000) as well as the Journal for Pathology Informatics (2010).

“Pathology was where I started, and pathology has really embraced informatics as a major part of the way pathologists practice now,” he says. “I’m very lucky to be a part of that evolution.”

After 15 years of surgical pathology practice coupled with running the laboratory information systems at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, Becich was asked to chair the university’s first Department of Biomedical Informatics in 2006. At the time, it was the 13th such program in the country, and informatics departments and institutes have continued to expand to approximately 30 today. He explains that biomedical informatics helps makes use of the vast amounts of information collected in the process of patient care.

“We have unlocked the value of all that data for research,” he says.

Along the way, his department has become one of the top biomedical informatics programs in the nation and has helped train scores of young people in the field — from high school all the way through graduate studies. He helped create a summer biomedical informatics program at the University of Pittsburgh for high school students that acts as a feeder program into the university’s undergraduate bioinformatics program.

“I encourage medical students, PhD students, undergraduates, and even high school students to get informatics under your belt and be facile with it,” he says. “It’s a critical skill set for career progression in our data-driven world.”

Stoking start-ups

Though his focus has been on academics, Becich has also enjoyed consulting with other academic centers, cancer centers, and companies to figure out how to use artificial intelligence and other cutting-edge informatics technologies to improve clinical care and discovery in medicine. For example, he recently collaborated with the French start-up Owkin to develop ways to use artificial intelligence to identify which mesothelioma tumors may be amenable to treatment. He has also created four start-up companies of his own, including the aforementioned SpIntellx.

Becich also leads the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center Enterprises, which acts like an “angel investor” to fund faculty-led start-ups, and the Center for Commercial Applications of Health Care Data, which provides early stage research to investigators from University of Pittsburgh and Carnegie Mellon University to develop technology that uses clinical data to inform medical decision-making and to integrate such new tools into healthcare. This program, called the Pittsburgh Health Data Alliance, is helping translate faculty research innovations into company startups (like SpIntellx).

“Industry-academic partnerships are really an important part of the future to bring more resources into universities,” he says. Although he acknowledged potential pitfalls, he says well-managed partnerships can yield innovation and entrepreneurship.

Where personal meets professional

Becich says his experiences at Northwestern played a transformative role in both his personal and professional life. Most importantly, he met his wife Barbara Dappert Becich, ’79 BA, during their undergraduate studies at Northwestern. A psychology major who earned her medical degree at Rush University, she recently retired after a long career as a neurologist. They have been married 41 years and have three accomplished children (Nicole, Mikayla, and Michael).

“None of this would have been possible without the support of my family,” he says.

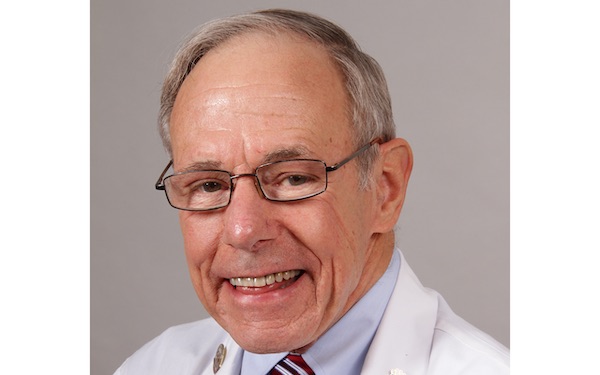

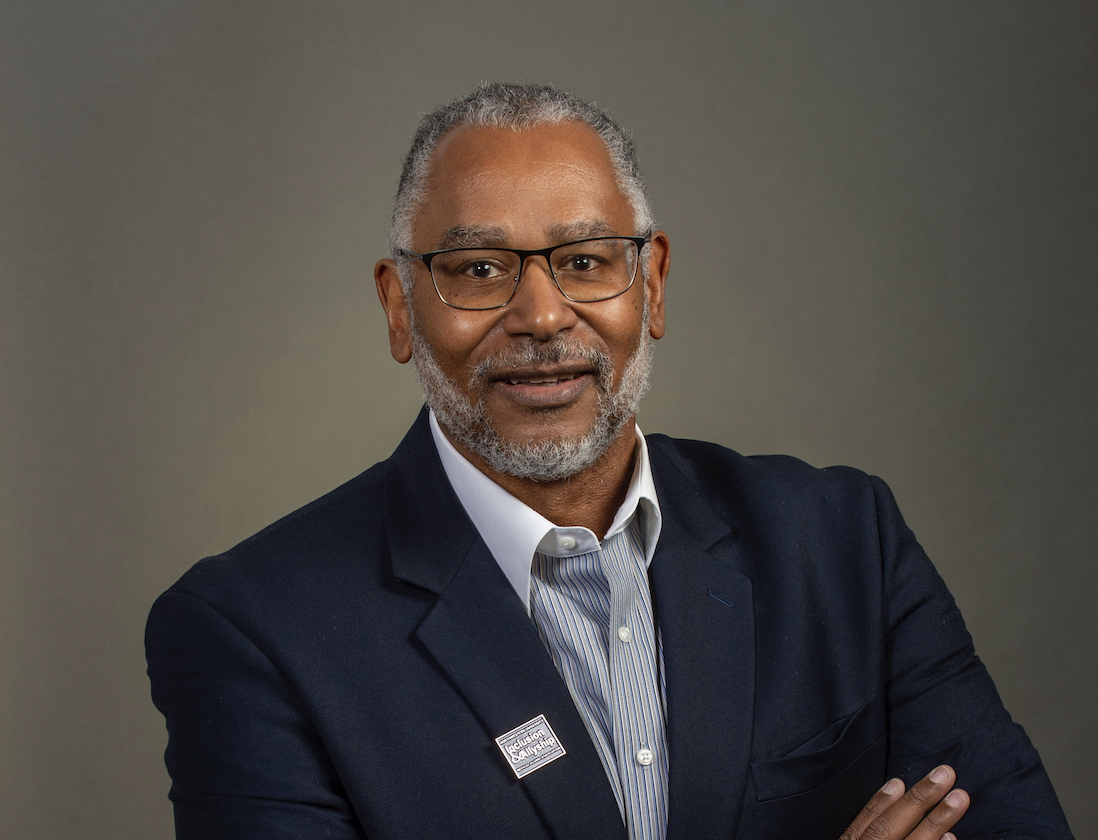

He also credits his mentors and former Department of Pathology chairs Janardan Reddy, MD, and Dante Scarpelli, MD, PhD, with shaping his career and helping train him to be an innovative researcher.

“Northwestern has always been a home to me,” he says. Now, he’s pleased to be able to give back by serving on the external advisory board for the Northwestern University Clinical and Translational Science (NUCATS) Institute.

He says the most gratifying part of his career has been training young people and being of service to many other physicians and scientists.

“It has been a blast,” he says. “You’re around smart people, you get to use technology, you can be an entrepreneur and, most importantly, you can have a very satisfying life of service to other people through innovation in medical research.”