For Every Man

Northwestern investigators make critical impact on prostate cancer research and care.

by Cheryl SooHoo

Prostate cancer remains persistently common — second only to skin cancer — for American men. One in eight men in the United States will face a prostate cancer diagnosis in his lifetime, and more Black men disproportionately develop and die from the disease than white men. While many patients with this typically slow-growing disease can live long, healthy lives, prostate cancer still kills some 33,000 each year.

“The mortality rate has actually declined in the past decade due to the gains we’ve made in diagnosis and treatment,” says Edward Schaeffer, MD, PhD, chair of the Department of Urology, the Edmund Andrews Professor of Urology, and director of the Polsky Urologic Cancer Institute of the Robert H. Lurie Comprehensive Cancer Center of Northwestern University, who credits enhanced screening as well as a plethora of recently FDA-approved prostate cancer drugs.

Pursuing diverse lines of inquiry, Feinberg investigators continue to make new discoveries that offer promise for more effective therapies. From teasing out the biological and social determinants of health disparities to developing the first precision medicine treatment, clinicians and scientists from the Lurie Cancer Center are dramatically changing the landscape for all men with prostate cancer.

Understanding Racial Disparities

Even with recent progress, Black men and men of African ancestry in the United States have a 1.8-fold increased risk of receiving a prostate cancer diagnosis compared to white men — and men of other races. And the disease is 2.5 times deadlier for African Americans. Fifteen years ago, Schaeffer began investigating this complex disparity on a molecular level when he noted poorer outcomes for some of his African American patients. More specifically, he says, “Black men with prostate cancer often had more aggressive cancers and experienced disease recurrence more frequently than other patients.”

No single reason accounts for the disproportionate impact of prostate cancer on Black men and in particular, African American men. The goal of better understanding racial disparities has taken the Schaeffer research team down multiple interconnected research paths that meld biological and socioeconomic factors. For example, the group has observed specific gene mutations associated with more aggressive disease progression and anatomic differences in tumors in men of African ancestry. In a 2019 study, the Schaeffer lab found that with similar access to care and standardized treatment, Black men with localized prostate cancer had just as good if not better outcomes than their white counterparts. And earlier this year, a Schaeffer-led group discovered that a specialized type of immune cell, a plasma B-cell, was present in much higher concentrations in aggressive prostate cancers from Black men. This finding may provide the mechanism for why immunotherapy seems to work better for Black men with advanced prostate cancer than for white men.

The goal of better understanding racial disparities has taken the Schaeffer research team down multiple interconnected research paths that meld biological and socioeconomic factors.

In a new study published in the February issue of Nature Communications, the investigators analyzed 1,300 tumor samples annotated with self-identified race or genetic ancestry. They found, in general, that tumors from Black men had more plasma cells compared to the tumors from white men and that men with enhanced plasma cells had improved cancer survival. The work further suggests that enriched plasma cell content could be a marker for enhanced responsiveness immune-based therapies. Accordingly, testing for plasma cell content in prostate cancer could lead to future immune-based precision medicine treatments for all men with localized aggressive and advanced, lethal prostate cancer.

“T-cells have always been the star child when it comes to immuno-oncology. Only very recently have plasma B-cells taken center stage and become strongly linked to tumor immune responsiveness,” Schaeffer says. “We saw an opportunity to be color blind and take a deep dive into whether having a lot of plasma cells in prostate cancer had any connection to living longer.”

Building on this work, the Schaeffer team plans to further evaluate the power of plasma cells by developing immunotherapy-focused clinical trials for treating prostate cancer.

First, Do No Harm

Active surveillance has emerged as a strategy to ensure the best quality of life for men with favorable-risk prostate cancer. While necessary for treating advanced disease, surgery and/or radiation can come with serious side effects such as incontinence, erectile dysfunction, and infertility. For many men, taking a “wait and see” approach is a more palatable alternative for addressing a disease that may never harm them.

Tumor profiling gives useful insight into the aggressiveness of a patient’s cancer by predicting the probability of bad outcomes. Commercial assays such as the Oncotype DX Genomic Prostate Score (GPS) help inform clinical decision-making about active surveillance and other options. Validated in mainly white populations, genomic testing has been shown to increase patient acceptance of active surveillance. Yet in a 70 percent Black population, tumor profiling had a dampening effect, according to a new study conducted by Adam Murphy, MD, MBA, assistant professor of Urology and Preventive Medicine, in collaboration with University of Illinois investigator Peter Gann, MD, ScD.

1 in 8

men in the United States will be diagnosed with prostate cancer.

33,000

people are killed by prostate

cancer each year.

1.8x

increased risk among Black men and men of African ancestry in the United States of receiving a prostate cancer diagnosis compared to white men and men of other races.

2.5x

deadlier for African Americans.

In one study, part of a larger trial called “Engaging Newly Diagnosed Men About Cancer Treatment Options (ENACT),” investigators recruited 200 men from three public Chicago hospitals. Participants fell into the category of very low to low-intermediate prostate cancer risk, which made them good candidates for active surveillance. Interestingly, the scientists found that low-literacy patients were less likely to choose this treatment option when presented with risk data about their tumor. While 88 percent of participants who didn’t receive tumor profiling opted for active surveillance, only 77 percent who received GPS results chose active surveillance. Additionally, men with low health literacy were more than seven times less inclined to accept active surveillance compared to those with high health literacy.

“Low literacy’s impact was unexpected,” says Murphy, who believes that fear of any cancer may persuade some patients to rid their body of the disease as soon as possible despite the consequences. “The finding indicates that medical practitioners need to do a better job counseling patients about their options so they can make informed decisions.”

Published in the April issue of the Journal of Clinical Oncology, the study also detailed two other strong predictors of accepting active surveillance: a family history of prostate cancer and insurance coverage. “A social determinant of health, insurance makes it easier for patients to comply with ongoing PSA testing, prostate exams, and biopsies that are all a part of active surveillance,” Murphy says.

More Precise Treatment

Patients with cancers of the breast, ovaries, lung, and pancreas have benefited from innovative therapies that precisely target specific genetic mutations. Not so for prostate cancer, an equally common cancer — until now. Last fall, Northwestern Medicine investigators and international collaborators reported in the New England Journal of Medicine ground-breaking results from the PROfound phase III clinical trial. They showed for the first time that genetically-targeted treatment can extend the lives of men with metastatic prostate cancer that has spread to the bone and elsewhere despite other previous therapies.

Ground-breaking results showed for the first time that genetically-targeted treatment can extend the lives of men with metastatic prostate cancer that has spread to the bone and elsewhere despite other previous therapies.

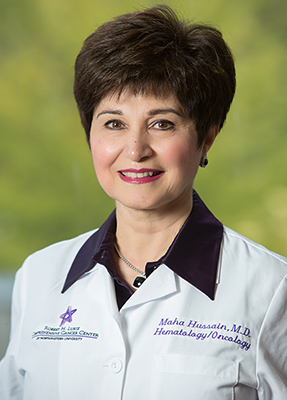

The team, led by Maha Hussain, MBChB, deputy director of the Lurie Cancer Center, the Genevieve E. Teuton Professor of Medicine in the Division of Hematology and Oncology, and principal investigator of Lurie Cancer Center’s Specialized Program of Research Excellence (SPORE) in prostate cancer, evaluated the drug Olaparib, already FDA-approved for the treatment of breast, ovarian, and pancreatic cancers. The drug works by blocking PARP, a protein that cancer cells use to repair their damaged DNA. Without PARP, the cancer cells die. Investigators found that Olaparib, a PARP inhibitor, extended the lives of men with metastatic, hormone-resistant prostate cancer. The clinical trial preselected participants based on their specific genetic mutations that result in defects in DNA repair. These alterations are mostcommonly found in the BRACA 1, BRACA 2, and ATM genes, says Hussain, co-principal investigator of the PROfound trial. “Our finding opens the door much wider to ushering in a new era of better personalized therapies and precision medicine for prostate cancer,” she says.

Another important, more early-stage discovery has been made by Sarki Abdulkadir, MD, PhD, the John T. Grayhack, MD, Professor of Urological Research and vice chair for research in the Department of Urology. In work published in Cancer Cell, Abdulkadir and colleagues describe a new strategy to slow treatment-resistant prostate cancer by suppressing the elusive MYC oncogene, which, he says, has been deemed “undruggable”.

Inhibiting an epigenetic regulator called DOT1L reduced growth of human prostate tumor cells while sparing healthy cells, says Abdulkadir, who was senior author of a study published in Nature Communications last fall and is, along with Hussain, principal investigator of the SPORE in prostate cancer at the Lurie Cancer Center, recently renewed by the National Cancer Institute.

“This could be really good for patients with treatment-resistant prostate cancer,” Abdulkadir says.

“We have entered a “new world order” in the care of advanced prostate cancer,” says Hussain. “I am delighted that we continue to make major steps in impacting this cancer. Investment in research, not wishful thinking is what will cure cancer. Critical to that is the partnership with patients and their families to achieve the ultimate goal.”

Advances in Screening

Introduced in the late 1980s, prostate-specific antigen (PSA) screening helped detect prostate cancers earlier and in their most curable stages. But by the early 1990s, wide-spread PSA testing became controversial. The lack of specificity of PSA and frequent use of prostate biopsy led to over-detection, especially of lower-risk disease that was often over-treated. In too many cases, men needlessly suffered treatment side effects such as incontinence and sexual dysfunction. Today, screening has evolved a great deal, according to Ashley Ross, MD, PhD, associate professor of Urology. He discusses the latest approaches to prostate cancer screening to ensure the “cure is not worse than the disease.”

Why is PSA testing still important?

It narrows the field of who is at risk. PSA screening still serves as a reasonable first step toward a potential prostate cancer diagnosis. A high PSA number doesn’t automatically mean a man has prostate cancer. It could be he has an enlarged prostate or infection. Even if cancer cells are present, men often have indolent, nonlethal disease. Because some prostate cancers can progress slowly, the decision to treat in men with limited life expectancy is nuanced.

How has a tiered approach improved screening and diagnosis?

Over the last two decades, we’ve developed a variety of more sophisticated urine, blood, and imaging tests that are more accurate than PSA. For example, use of an additional serum test, like the Prostate Health Index (PHI), can help guide detection of important prostate cancers while avoiding unnecessary biopsies. Imaging with multi-parametric MRI can not only provide information regarding the risk of cancer presence but also its location. At Northwestern, we often use a tiered approach: an abnormal PSA test leads to a PHI score, which, if abnormal, is followed by magnetic resonance imaging and then a decision regarding biopsy. Elevated PSA no longer equals biopsy.

What does the future hold?

A key goal of screening remains reducing avoidable biopsies, while identifying clinically significant cancers early when they are most curable. Prostate cancer has been shown to have a large genetic component. Northwestern scientists and others around the world have begun investigating the utility of polygenetic risk scores — looking at hundreds of genes — in prostate cancer screening. Still to be evaluated in clinical studies, this new tool could allow us to more accurately predict men at increased risk of prostate cancer. It could aid us in promoting screening while also identifying those men — a segment of the population — for whom we can take a relaxed or no prostate cancer screening approach.