Home / Alumni News / Carving Out a New Path

Carving Out a New Path

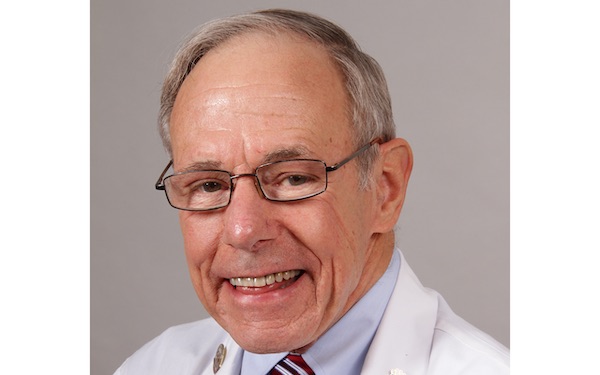

Charlotte S. Yeh, ’71 BS, ’75 MD, chief medical officer at AARP Services, Inc., has carved out a unique career path from the emergency department to consumer-oriented wellness.

Charlotte S. Yeh, ’71 BS, ’75 MD, spent her first day as a surgical intern at the University of Washington in Seattle working in a community emergency department. That initial trial by fire introduced her to the specialty she would fall in love with and practice for three decades.

“You could create order out of chaos,” she says. “People came in scared, frightened, and you had a chance to make a difference in their lives.”

Each time she rotated through the emergency department during her two years of surgical residency, she found herself beaming from ear to ear, so she decided to change her career trajectory. But the change wouldn’t be so straightforward. Emergency medicine would not become an officially recognized specialty until 1979.

Yeh had to create her own path — something she has done time and time again over her five-decade-long career. She has gone from being among the first cohorts of emergency residents in the country to a leader and advocate in the field. Not content to stop there, she has plunged into the world of policymakers and payors to expand her impact on patient care, and, more recently, she has worked to empower older adults to live healthy, fulfilling lives.

CHANGE AGENT

Yeh decided to become a physician at age 5 after a close friend required tonsilitis treatment. Few women were in the field then, but she found a role model in a family friend who was a physician-scientist. Yeh planned to follow in the woman’s footsteps, but she discovered that she enjoyed hands-on clinical care through Northwestern’s Honors Program in Medicine and shifted her focus “from test tubes to people.”

“Thank goodness for Northwestern,” she says. She credited the strong clinical training at Northwestern for giving her the confidence to know she was doing right by her patients even under high pressure situations in the emergency department.

During her surgical residency at the University of Washington, she witnessed the profound impact of Seattle’s early investment in training the public in cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) and deploying emergency medical services. She remembers a person who had a cardiac arrest just outside city limits and was kept alive by a bystander conducting CPR. They were stabilized and transported to the hospital by paramedics, then walked out of the hospital after receiving care.

“The emergency department is such a barometer of what works and what does not in healthcare and the community,” she says.

Her experiences in Seattle solidified her decision to work in the emergency department despite criticism from some individuals that she was “throwing her career away.” She transferred to the general surgery program at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA). Soon after, UCLA created an emergency department residency program, and Yeh became part of its inaugural class.

“There is no greater high than when you are successful at caring for someone in the emergency department and no lower low than when you are not,” she says.

In 1980, Yeh joined the faculty at Newton-Wellesley Hospital, a community hospital on the outskirts of Boston, where she helped create the first emergency department to provide 24/7 emergency medicine residency-trained attending physicians. She served as emergency department chief from 1986 to 1994. She also helped create the first full academic department of emergency medicine in Boston and the first to provide 24/7 full-time emergency medicine-trained attending supervision in an academic medical center in Boston at Tufts Medical Center. She served as the department’s physician-in-chief for eight years, from 1990 to 1998.

Throughout her career, she witnessed some of the holes in the safety net that emergency departments provide for their communities. She remembers vividly a woman bleeding profusely in the lobby of one emergency department where Yeh worked before moving to Massachusetts. Registration staff wanted to send the woman by ambulance two hours away to the county hospital because she could not pay. Instead, Yeh insisted on providing immediate care, because no one should be turned away because of an inability to pay.

“When you see people and hear their stories, it inspires you to advocate for change,” she says.

She became involved with advocacy at the American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP), where she helped advocate for the passage of the Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Act (EMTALA). The federal law enacted in 1986 requires hospitals to provide lifesaving emergency care regardless of the patient’s ability to pay. She was the third woman to serve on the ACEP’s Board of Directors and was the organization’s vice president from 1992 to 1993.

She served on the Board of Directors of the Massachusetts Seat Belt Coalition from 1985 to 1990 and advocated for laws requiring seat belts and provided testimony on the tremendous difference they make for people involved in car accidents. Though her testimony often brought policymakers to tears, it did not change policy. It was not until she started including information on the costs of treating individuals who were not wearing safety belts that she saw the needle move.

“It is not enough to tell the story,” she says. “We have to show it is costing us money if we do not.”

Though she loved the three decades she worked in emergency departments, she began to feel she could make a bigger impact elsewhere. “I was just catching people as they fell through the cracks,” she says. “I needed to go upstream.”

POLICY PIVOT

The systems-level thinking, calm, and patience Yeh developed in the emergency department proved to be assets as she pivoted her career into the world of policy full-time. She started as medical director of Medicare Policy for the National Heritage Insurance Company, a contractor processing Medicare part B claims, in 1999. She then served as regional administrator at the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) in Boston from 2003 through 2008. In that role, she helped promote Medicare’s newly created Part D prescription drug coverage to seniors.

She also took on other leadership roles, serving on the American Hospital Association’s board from 2002 to 2003 and the Blue Cross Blue Shield of Massachusetts Foundation Board from 2001 to 2018. Her work in Massachusetts in the early 2000s gave her a front-row seat to the state’s efforts to expand health insurance coverage, which eventually provided the blueprint for the Affordable Care Act. As CMS regional administrator, she supported the waiver to allow the program to proceed.

“It was nice to be one little piece in all the people that worked on that,” she says.

Since 2008, she has been the chief medical officer of AARP Services, Inc., which helps develop products and services for older adults — a role that has allowed her to focus on consumer advocacy.

“It is about going back to my roots and helping people live their best lives and stay healthy,” she says. But instead of helping one person at a time, she is working to help the more than 100 million Americans who are 50 and older, and their families, she says.

She has shifted her focus to solving “upstream” problems with the hope of preventing people from ever needing to visit the emergency department. For example, she’s worked on initiatives helping older people, their families, and caregivers navigate the health system that reduced hospitalizations and associated costs. Her work at AARP has gained her national recognition, including as one of Modern Healthcare’s 50 Most Influential Healthcare Executives in 2021. She also serves on the Dementia Discovery Fund Scientific Advisory Board, the Personal Connected Health Alliance Board of Managers, the Board of Directors for The Schwartz Center for Compassionate Care, and the Board of Directors for the Coalition to Transform Advanced Care.

Her current focus at AARP is helping older adults reduce social isolation and loneliness and help them find a renewed sense of purpose, which she noted are all keys to staying healthy. Her own battle to recover and relearn how to walk after being hit by a car a few years ago has made her even more passionate about her work. Since the accident, she has learned to ski and has taken up biking, boxing, and scuba diving.

“I have learned a lot of new things to keep me busy, active, and making the most of my life,” she says.