Making Dementia ‘Just a Memory’

Robert Vassar, PhD, takes over the long-running Mesulam Center as Alzheimer’s treatments finally make a breakthrough.

By Emily Ayshford

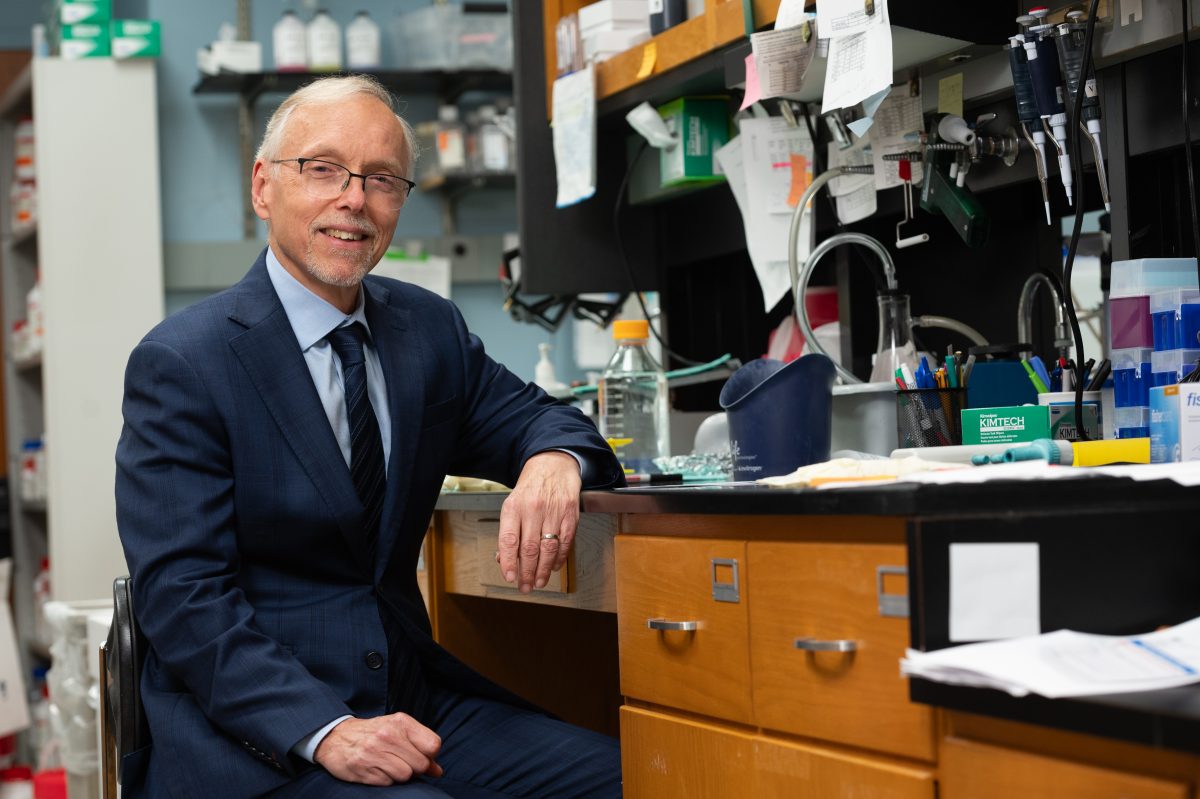

Robert Vassar, PhD, was just a few years out of college when his mother was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease.

It was 1983, and his mother was just 61. At the time, there were no treatments. Scientists and physicians did not yet even understand the mechanisms behind the disease. Vassar, who had been pre-med as an undergraduate biology major at the University of Chicago, had ultimately decided that a career in medicine wasn’t the career path for him. But the diagnosis galvanized him.

He enrolled in graduate school at the University of Chicago to study molecular genetics and cell biology, starting him on a winding path that would include molecular research that contributed to a Nobel Prize and the discovery of an enzyme that could ultimately lead to new treatments for Alzheimer’s.

Now, as he takes over as director of Feinberg’s long-running Mesulam Center for Cognitive Neurology and Alzheimer’s Disease, he’s excited for the future of the field. The FDA has recently approved new treatments for Alzheimer’s, and recent research shows that a combination of therapies might be the key to preventing the disease altogether. Research at the center is at the forefront of understanding the pathogenesis of dementias.

One day, we will be able to say dementias like Alzheimer’s disease are just a memory.

Robert Vassar, PhD

“We had nothing for my mom,” says Vassar, the Davee Professor of Alzheimer Research in the Ken and Ruth Davee Department of Neurology and in the Department of Cell and Developmental Biology. “I’ve devoted my life to trying to discover the cause of this disease and to find how we can stop it. It’s all in her memory and in her honor. One day, we will be able to say dementias like Alzheimer’s disease are just a memory.”

FROM SKIN DISEASE TO ALZHEIMER’S DISEASE

When Vassar entered graduate school at the University of Chicago in 1986, he had dreams of studying the genetic basis of Alzheimer’s disease. But the field wasn’t ready; there was not yet any genetic understanding of the disease. So, Vassar studied skin disease at the molecular and genetic levels, learning the tools of the trade.

When he received his PhD in 1992, he headed to a postdoctoral fellowship at Columbia University in the lab of Richard Axel, MD, professor of Pathology and Biochemistry at Columbia University and investigator at the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, where he studied the neurological underpinnings of our sense of smell. He figured out how olfactory receptors were connected to the olfactory bulb — the first relay station of our sense of smell. The work contributed to Axel receiving the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 2004 for decoding olfaction.

“It got me back into neuroscience, using the tools of molecular genetics to decipher problems,” Vassar says. “Then I was ready for Alzheimer’s disease.”

He joined the biotech company Amgen in 1996, building an Alzheimer’s research lab from the ground up. By then, scientists had discovered that the beta amyloid protein formed amyloid plaques in the brains of people with Alzheimer’s disease. Moreover, mutations in certain genes caused genetic forms of the disorder by increasing the production of beta amyloid. That, combined with tangles of Tau proteins, seemed to be responsible for cognitive decline.

Vassar designed an experiment to screen genes that increased beta amyloid, ultimately discovering BACE1 (beta-site APP-cleaving enzyme). This enzyme, it turned out, is responsible for generating the beta amyloid that forms amyloid plaques. Vassar’s research paper on the discovery has since become a classic in the field.

“We ended up starting a whole field of BACE research,” Vassar says.

JOINING THE MESULAM CENTER

Vassar left the biotech industry to join Northwestern in 2001, continuing his BACE research. Drugs that inhibited the BACE protein advanced in clinical trials, and Vassar had high hopes that the drugs would ultimately prevent amyloid plaques from forming and perhaps provide a new treatment for the disease. By then it had been nearly 20 years since his mother was diagnosed, and scientists had yet to find new therapies for devastating dementias.

But it wasn’t yet meant to be. The high dosages of the inhibitors caused patients’ cognition to decline even more — the exact opposite of what scientists had hoped they would do. “That was a big disappointment,” Vassar says. Still, he and his colleagues in the field think the inhibitors may be safe at a lower dosage that reduces beta amyloid production enough to prevent Alzheimer’s, a goal toward which they are now focused.

Despite the disappointments, Vassar continues his research on BACE, and studies the molecular and cellular mechanisms of Alzheimer’s disease. “The more we understand about the pathogenesis at a molecular level, the more we can identify new drug targets that we would then be able to therapeutically intervene with and help alleviate Alzheimer’s disease,” he says.

Throughout his time at Northwestern, Vassar has been a key member of the Mesulam Center, a hub for dementia research and personalized diagnostic and clinical care. The center was founded in 1996 as a National Institutes of Health-funded Cognitive Neurology and Alzheimer’s Disease Center (CNADC P30). At the helm was Marsel Mesulam, MD, a giant in the field of neurology. In the 1980s, Mesulam had identified primary progressive aphasia (PPA), a rare dementia that affects a person’s language, as a distinct syndrome. As director of the center, he saw funding be renewed without interruption for more than 25 years, and the name of the center was changed to honor him in 2018.

The more we understand about the pathogenesis at a molecular level, the more we can identify new drug targets that we would then be able to therapeutically intervene with and help alleviate Alzheimer’s disease.

Robert Vassar, PhD

When Mesulam decided a few years ago to step down, he wanted Vassar to take over “so he could introduce more molecular science to our already thriving clinical, neurocognitive, and imaging portfolios on dementia and brain aging,” says Mesulam, chief of Behavioral Neurology in the Department of Neurology and the Ruth Dunbar Davee Professor of Neuroscience. “Bob now has unique and enhanced opportunities to pursue this mission and integrate it with the other strengths of the center.”

Vassar ultimately took over in January 2023. “To me, it’s a great honor to follow in his footsteps,” Vassar says. “Those are huge shoes to fill.”

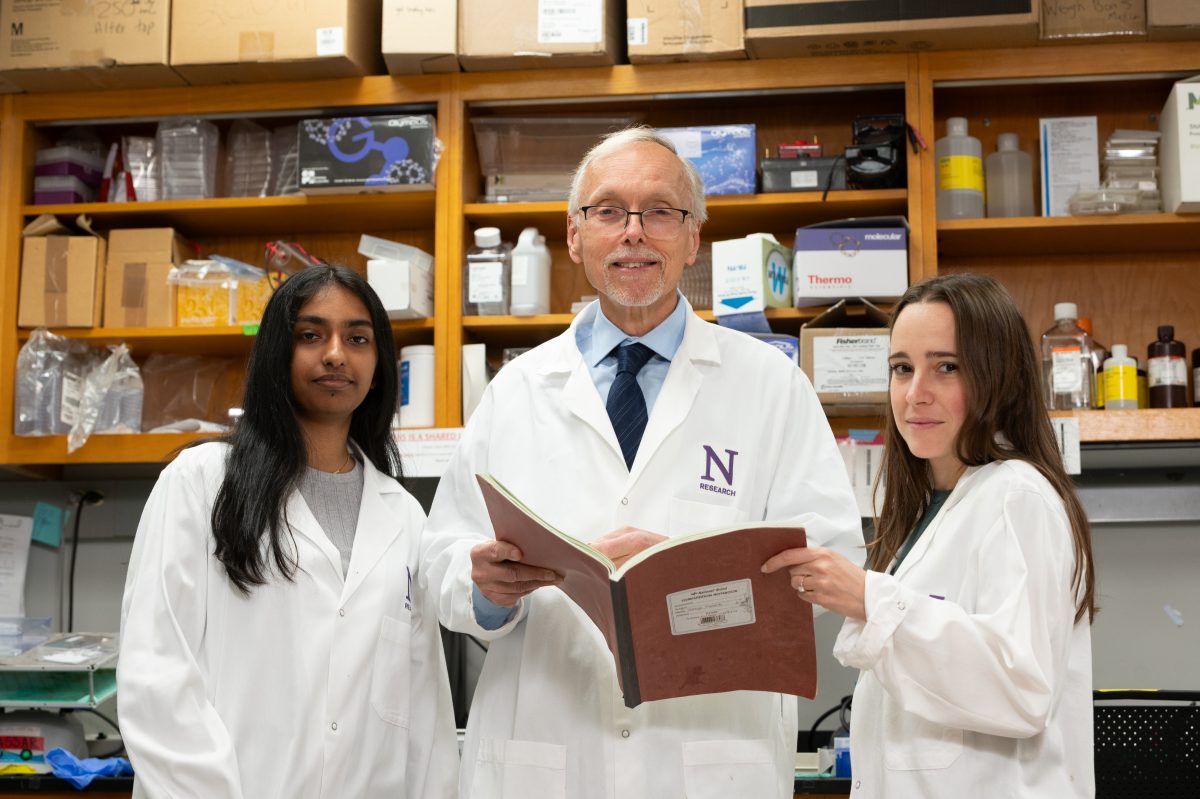

As director, Vassar hopes to encourage even more groundbreaking research at the center, especially by harnessing leading-edge technology such as single-cell RNA sequencing and transcriptomics. He also plans to encourage the center’s other successful research programs. Not only do scientists there study the pathogenesis of dementias in the brain, but they also study the brains of those who maintain youthful memory function. These so-called “SuperAgers” are adults over 80 who have the memory abilities of those in their sixties or even fifties.

“We’re looking at all aspects of their lives — their lifestyles, their genetics — and following them over time to understand the secret of superaging,” Vassar says. “The hope is that it might stimulate how we can help people avoid age-related dementias.”

CREATING A TOOLKIT OF THERAPIES

The center is also involved in a clinical trial for the drug lecanemab (commercially known as Leqembi), which was recently approved by the FDA. The drug, an antibody, stimulates the brain’s microglial cells to remove amyloid plaques. About 70 percent of people on the drug have no more amyloid in their brains after a year.

Still, it has side effects, and it doesn’t cure the disease; patients ultimately find that the disease still progresses. But Vassar is hopeful that might be one tool in the toolkit against Alzheimer’s and dementia — one that he hopes will ultimately include BACE inhibitors. In his lab, he’s still researching BACE, hoping to find the right dose to make it safe and effective for patients.

With approved therapies and those on the horizon, it’s possible that one day those at risk for Alzheimer’s could take a blood test that could reveal the beginnings of amyloid plaque in their brain. Then, they could take a suite of therapies to stop progression.

“We’re going to end up with whole toolkits of different drugs that tackle different targets in the Alzheimer’s disease pathway,” Vassar says. “If we look at primary prevention, we could stop the production of beta amyloid and perhaps completely prevent the onset of Alzheimer’s.”

How far away that reality is remains to be seen. For now, Vassar is continuing his work — and ensuring his own health. Research shows that exercise and cognitive stimulation can both help and prevent Alzheimer’s. Most days, you can find Vassar and his wife in the gym, doing both cardiovascular and resistance workouts. He also loves to spend time with his three adult stepchildren and their children, as well as listen to jazz and hike at the Indiana Dunes.

“Having an enriched life is good for preventing Alzheimer’s,” he says. “My mother died in a vegetative state, and I’m doing everything I can to prevent myself and others from doing the same. We’ve had a lot of false starts and setbacks, but the future is bright.”