Master of Mitochondria

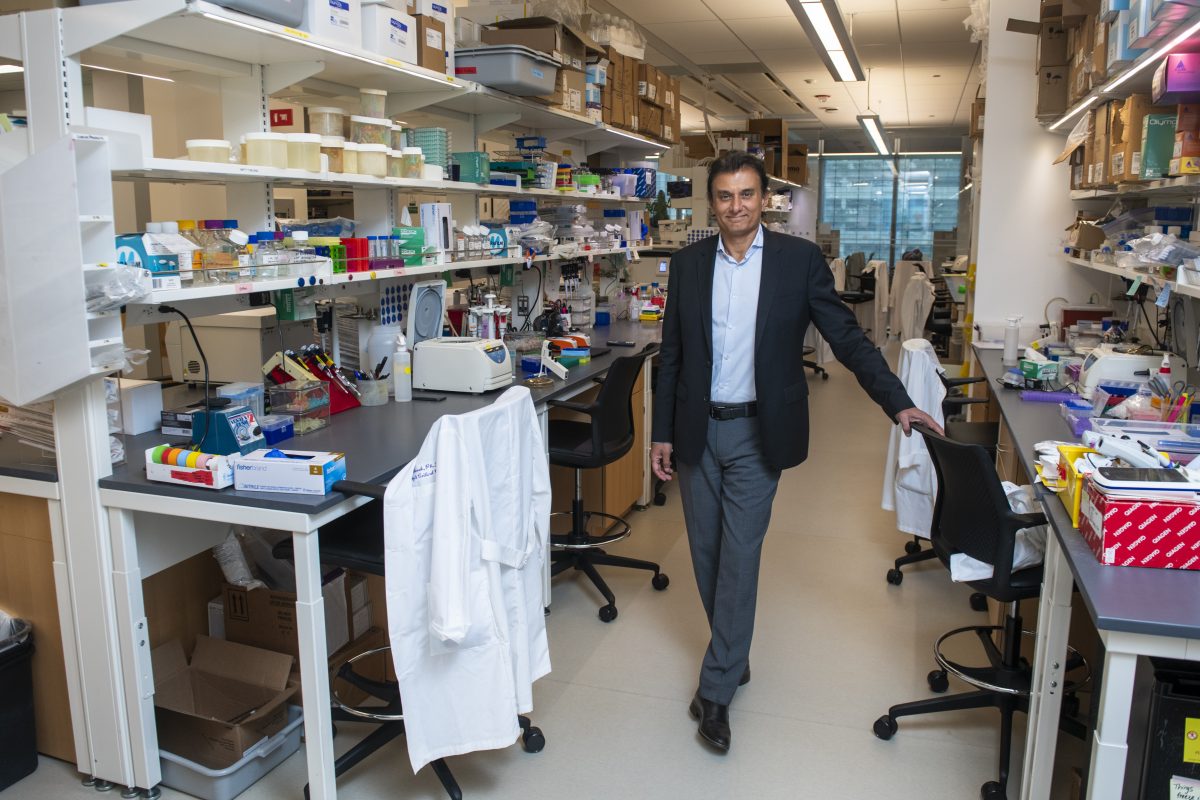

Navdeep Chandel’s research revealing how mitochondrial signaling contributes to health and disease was recognized with the prestigious Lurie Prize in Biomedical Sciences.

By Bridget M. Kuehn

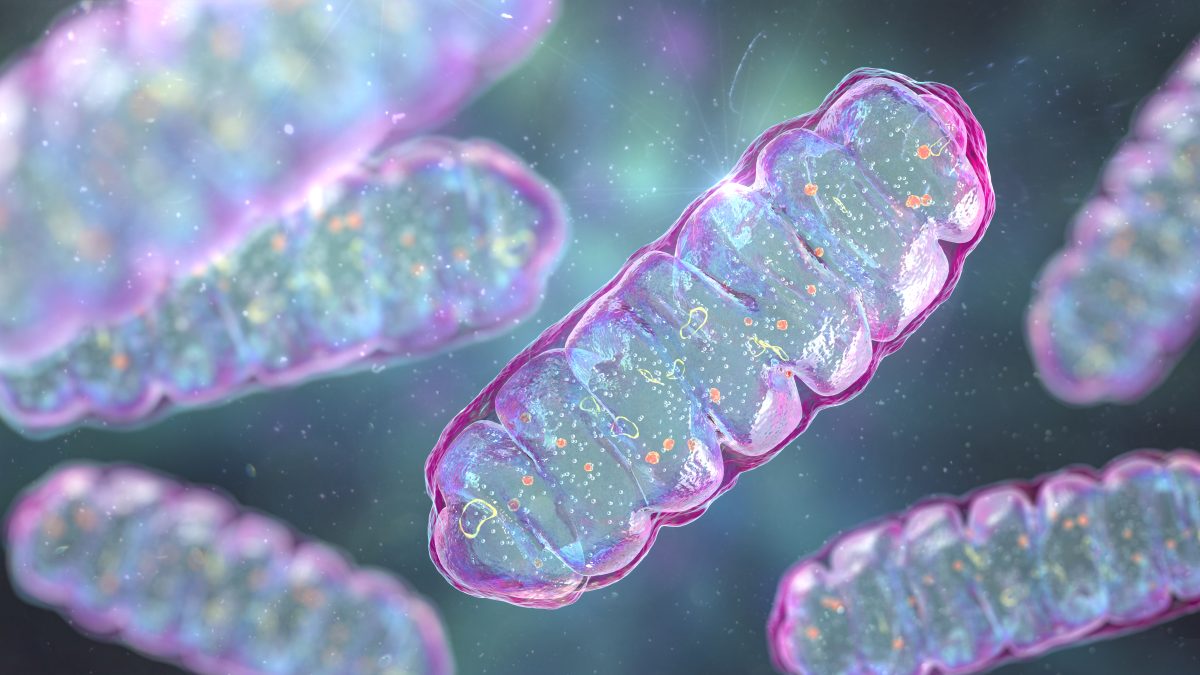

Mitochondria are often described as the “powerhouses” of the cell, generating most of the energy needed to power the cell’s biochemical reactions.

During the past century, investigators earned accolades for defining this role. But as this knowledge was inscribed in textbooks, the field faded from the limelight by the 1980s.

Navdeep Chandel, PhD, the David W. Cugell, MD, Professor and professor of Medicine in the Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care and of Biochemistry and Molecular Genetics, set out to discover that mitochondria had other crucial roles beyond their function in energy production. His research demonstrating the crucial signaling role mitochondria play in health and disease is helping thrust the field back into the spotlight.

Recently, his efforts have been rewarded. Chandel and Vamsi Mootha, MD, a professor of Systems Biology and Medicine at Harvard Medical School who studies mitochondrial genes link to disease, were named the 2023 recipients of the Lurie Prize in Biomedical Sciences by the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health (FNIH).

“It’s recognition that the field of mitochondrial research has reemerged into a prominent role in the world of medicine,” Chandel says. “It has come back beyond what is in the textbook.”

The Lurie Prize, which comes with a $50,000 honorarium, is in its 11th year and recognizes outstanding achievement by promising scientists aged 52 years and younger. The award is made possible by a donation to FNIH from philanthropist Ann Lurie, president of the Ann and Robert H. Lurie Foundation.

For Chandel, the award is more than an individual honor. He is thankful to Ali Shilatifard, PhD, chair of the Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Genetics, who nominated him for the Lurie Prize. Chandel also says he is fortunate to be in the Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care, which provides a collaborative and nurturing environment. That environment was created by former division chief and the Ernest S. Bazley Professor of Asthma and Related Disorders, Jacob Sznajder, MD, and continues to thrive under the current leadership of Scott Budinger, MD, chief of Pulmonary and Critical Care in the Department of Medicine.

If you can identify the signals, we can try to fix them with targeted therapies. That will be the rest of my life’s scientific pursuit.

Navdeep Chandel, PhD

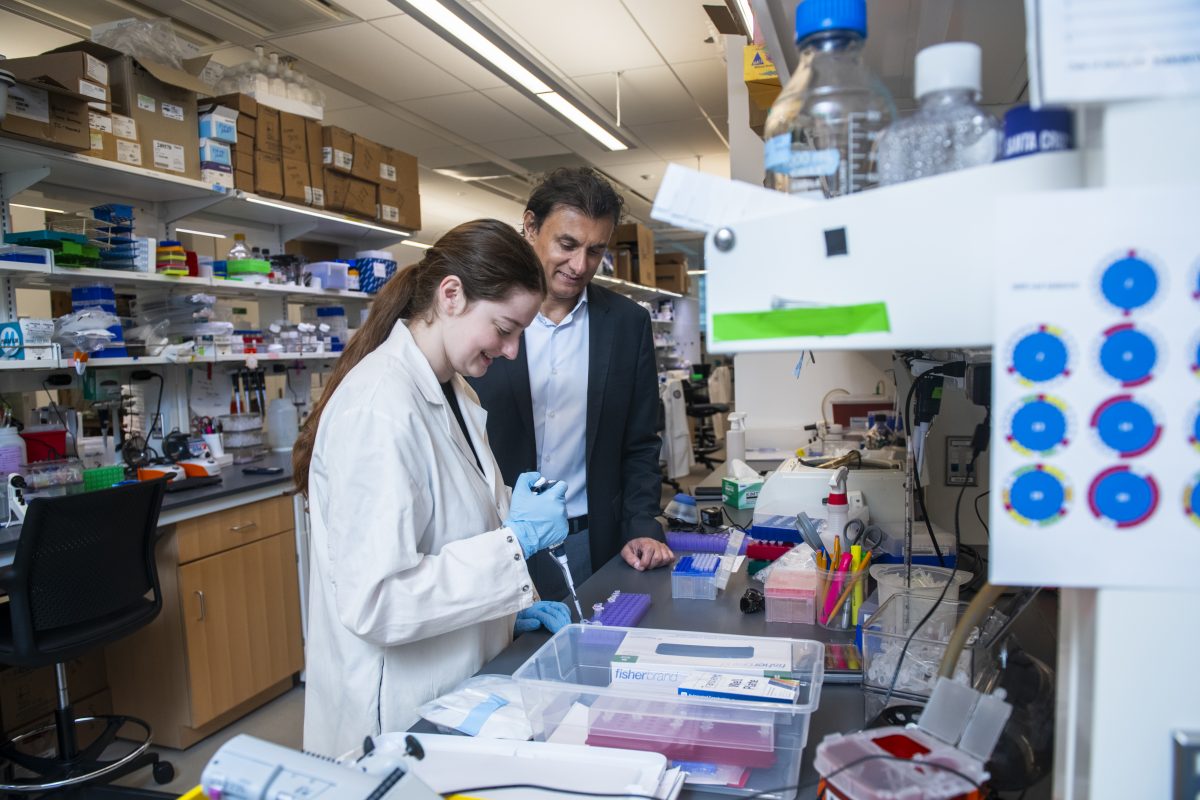

The award is also a recognition of the work of his past and current laboratory members, many collaborators, and mentors including Paul Schumacker, PhD, professor of Pediatrics, of Cell and Developmental Biology, and of Medicine. “You are only as good as the people in your lab,” he says. “The dynamic energy of the people you work with makes the difference.”

BEYOND ENERGY PRODUCTION

Mitochondria use oxidative phosphorylation to produce ATP, an energy source used to fuel the cell’s activities. But early in his career, Chandel started questioning whether there might be more to mitochondria than energy production. As a PhD candidate at the University of Chicago, Chandel studied a mitochondrial enzyme called cytochrome C oxidase, which is central to energy production. In 1996, a pivotal discovery showed that mitochondria release cytochrome C oxidase, triggering cell death. “If it is in the wrong location, it causes cell death,” Chandel explains. “That is a signal.”

That study inspired Chandel to focus on mitochondria’s role in cellular signaling when he launched his own laboratory at Northwestern in 2000. He started by studying how hydrogen peroxide produced by mitochondria acts as a signaling molecule. Many scientists believed hydrogen peroxide production by mitochondria contributed to oxidative stress, causing aging, neurodegeneration, and other conditions like heart disease. But clinical studies that used antioxidants to counteract these effects failed.

“Sometimes antioxidants have made things worse,” Chandel says. “Either the antioxidants were not the right ones, or there is more to it.”

Chandel demonstrated that hydrogen peroxide produced by mitochondria acts as a signaling molecule essential to health. “You would not want to disrupt that,” he says. “Mitochondria generation of hydrogen peroxide is so fundamental to everything.” Chandel and his laboratory have begun applying their basic science discoveries to understanding the role mitochondrial signaling plays in many physiologic contexts and diseases.

“If you can identify the signals, we can try to fix them with targeted therapies,” he says. “That will be the rest of my life’s scientific pursuit.”

KICKING AROUND IDEAS

Chandel’s other obsession is soccer, and he plays the sport two to three times a week—something he hopes he can continue until at least age 60—and watches it as often as he can. “A lot of my life is built around soccer,” he says.

The sport is emblematic of how he practices science, emphasizing teamwork and collaboration. That has led to many productive collaborations at Northwestern that have helped make Chandel a highly cited scientist and led to discoveries about the role of mitochondria in lung disease, cancer, and immune related diseases.

“I am a master of one thing—mitochondria,” Chandel says. He often partners with other scientists to understand how mitochondrial signaling may contribute to the diseases they study.

I am a master of one thing—mitochondria.

Navdeep Chandel, PhD

For example, a recent collaboration with SeungHye Han, MD, MPH, assistant professor of Medicine, revealed that mitochondrial signaling is essential in lung cell development. In the experiments, Han knocked out the essential ATP-producing pathway in developing mice and found unexpectedly that the mice did not die immediately. Instead, they found that the mice’s lung cells did not differentiate appropriately because of chronic elevation of a stress pathway that eventually led to death.

“Stress pathways should turn on and off,” Chandel explains. “This particular stress pathway turned on and became hyper-activated.” When they gave a small molecule to the mice that tamped down the stress pathway but did not fix the metabolic effect on ATP production, the mice lived. The result suggests potential treatment strategies for rare developmental lung disorders involving these pathways.

Chandel is also working with his long-time collaborator Scott Budinger, MD, director of the new Simpson Querrey Lung Institute for Translational Sciences, to leverage basic science being conducted at Northwestern to help discover new therapeutics for lung disease. He noted that though it takes decades to translate basic science into the clinic, many recent therapeutic advances, such as cancer immunotherapies, mRNA vaccines and gene editing, are rooted in basic science discoveries.

He also works to understand how metformin, a medication widely used to treat metabolic diseases, may work by targeting mitochondria signaling molecules and temporarily turning on stress pathways controlled by mitochondrial complex 1. Previous studies from his lab and others have suggested that chronic inhibition of mitochondrial complex 1 may contribute to Parkinson’s, lung fibrosis, or a rare metabolic disorder called Leigh syndrome that affects the brain. However, he suspects that by temporarily reversibly inhibiting mitochondrial complex 1, metformin may help prepare the body for future stress.

Despite his recent accolade and his many publications in prestigious journals, Chandel says his greatest honor to date is receiving the 2013-2014 Ver Steeg Award, which recognizes a faculty member of the Graduate School of Northwestern University for excellence in working with students. Graduate students in his laboratory nominated him.

“It is still arguably the most touching award I will probably receive in my lifetime, and it is really important to me,” Chandel says. He has mentored 25 graduate students and served on 75 to 80 thesis committees. “Engaging with graduate students and inspiring them about science and making a new discovery together is the greatest feeling on earth,” he says.