Informing Policy

by GINA BAZER

Northwestern investigators leverage science to drive policy change.

Two Northwestern investigators — Linda Teplin, PhD, and Lori Ann Post, PhD — are at the forefront of some of the most complex and dire issues facing the United States today, blending rigorous scientific investigation and perseverance to put their findings in the hands of policymakers.

Pursuing data, against the odds

Twenty-five years ago, Linda Teplin, PhD, set off to do what most people told her would be impossible: the first-ever longitudinal study investigating the mental health and long-term outcomes of youth detained in the juvenile justice system.

“Everyone said, ‘You can’t do this. The kids won’t cooperate, and once they leave detention, you will never find them,’” says Teplin, who is vice chair for research in the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, director of the Health Disparities and Public Policy Program, and the Owen L. Coon Professor of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences.

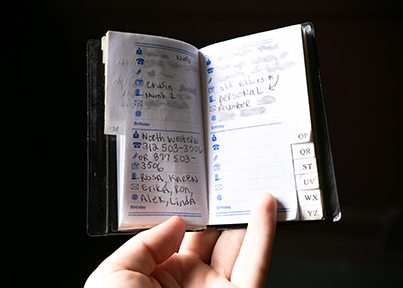

Undaunted, Teplin — along with her associate director, Karen Abram, PhD, and an interdisciplinary team that included biostatistician Leah J. Welty, PhD — developed the Northwestern Juvenile Project (NJP). The project followed a randomly selected sample of 1,829 youth who were arrested and detained in Cook County, Illinois, between 1995 and 1998. Interviewers used standard psychological assessments to query participants about their mental health, substance use, gang membership, firearm involvement, and more. And, says Teplin, “Nearly all of the children wanted to be interviewed.”

Youth were between 10 and 18 years old when Teplin’s team first interviewed them, and every one to two years, they were re-interviewed. Participation rates have been about 90 percent. Participants are compensated for their time, and sent birthday cards, holiday gifts, and baseball tickets donated by the White Sox organization — part of how the investigators maintain contact with them. However, Teplin says that’s not necessarily what motivates them. “Many have told us, ‘You don’t have to pay me. It’s enough that you listen.’ One of our participants wrote to us from prison, saying, ‘Thank you. You are the only people in the world who remembered my birthday.’”

Teplin has been awarded a cumulative $54 million from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and 22 other federal agencies and private foundations since NJP’s inception, and her team has gone to great lengths to retain their participants. “We go to their homes, we visit them in jail and prison,” she says. “We interviewed a participant during her dinner break from her job as an exotic dancer and someone else in her boyfriend’s garbage truck.”

The team’s findings over the years — published in journals including JAMA Psychiatry, JAMA Pediatrics, Pediatrics, and the American Journal of Public Health — paint a dire picture. The majority of the detained juveniles had one or more psychiatric disorders; by median age 32, more than 6 percent had died (many by homicide); only half had finished high school or its equivalent; and by median age 30, three-quarters of the sample had been incarcerated one or more times in an adult jail or prison.

African Americans fared the worst. “This is particularly disheartening because African Americans comprise about 13 percent of the population in the U.S., but account for more than 40 percent of youth and adults in corrections,” says Teplin.

Findings from the NJP have been cited in reports by the U.S. Surgeon General, used in amicus briefs to the Supreme Court, presented in congressional hearings, and widely disseminated by federal agencies and advocacy groups.

Their studies also impact policy. For example, data showing that nearly three-quarters of girls and two-thirds of boys entering detention had one or more psychiatric disorders, and half had a substance use disorder, helped spur development of tools used by correctional facilities to screen and treat detainees. Another finding, that girls had substantially different patterns of disorders than their male counterparts, led detention centers nationwide to implement gender-specific programs.

A surprising discovery, that non-Hispanic whites were more than 30 times more likely than members of non-white populations to have an addiction to “hard drugs” (like cocaine and heroin), helped generate support for policies that address the consequences of the “War on Drugs” for African Americans.

“Our findings added to the growing debate on how the war on drugs has affected African Americans,” says Teplin. “African Americans are less likely than other racial or ethnic groups to abuse hard drugs, yet African Americans are disproportionately incarcerated for drug crimes.”

“It’s a social class issue,” she adds. “When wealthy kids sell drugs, their schools usually call the parents first. Their parents may promise to obtain treatment for their child in exchange for leniency. They are also more likely to be able to afford an attorney if needed. In contrast, poor children are more likely to attend schools with ‘no tolerance’ policies. These schools call the police first, and the child is more likely to be arrested and detained. People presume that we study criminals, but that’s incorrect; we study poor people.”

Beyond detention: life after incarceration

Today, the number of original NJP participants has diminished to 1,561; 176 have died, many violently. Most of the participants are now in their late 30s. Many have returned to their communities; some have overcome their early challenges and are thriving, but many continue to be involved with the criminal justice system.

Many, too, have had children. And, last year, a new round of four grants from the NIH and the Department of Justice allowed Teplin, Abram, and Welty, along with Amélie Petitclerc, PhD, a developmental and clinical psychologist, and an assistant professor of Medical Social Sciences, to launch the next phase of their research — NJP: Next Generation. Next Generation will address critical questions. How does the parents’ involvement with firearms during their own adolescence affect that of their child? What are the collateral consequences (moving homes, changing schools, entering foster care) of parents’ incarceration for their children? In addition, are there intergenerational patterns in the development and persistence of substance use disorders?

“We hope to identify individual, family, and community characteristics that will help at-risk children become resilient to challenging circumstances,” said Abram. “Our findings will inform the development of new strategies to support families and communities.”

Erika Ostrander, MA, MS, the clinical research project manager for Next Generation, is currently assembling the team of interviewers who will interview both the original participants and their adolescent children.

Ten years ago, Ostrander was an interviewer herself, and the story of one young woman continues to haunt her. “She was arrested at the age of 13,” Ostrander says. “Back in the ’90s, children were more often tried as adults and given harsh sentences. The first time I interviewed her, she was in prison and about to be released. She was thrilled to be free. Yet when we spoke a couple years later, it was heartbreaking. Re-entering society had been so difficult, she said she would rather return to prison.”

Despite the devastating stories she hears, Ostrander is optimistic that Next Generation will precipitate change. “Our study will drive policy and help improve lives,” she says.

Teplin, too, focuses on the end goal. “Most large-scale longitudinal studies examine only patients or general populations. They omit correctional populations, who are likely to have the worst outcomes. Thus, findings are biased. Our studies address these omissions. Because we focus on correctional populations, our studies show how to increase resilience in the highest-risk populations. Large-scale epidemiological studies are the first steps needed to address disparities in incarceration and health,” she says.

We hope to identify individual, family, and community characteristics that will help at-risk children become resilient to challenging outcomes.

Karen Abram, PhD

Professor of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences

Out in the Field

The key to NJP’s longevity has been perseverance in tracking participants. For the past 25 years, the project — staffed by anywhere from 20 to 50 people, both in the office and in the field — has resulted in about 18,000 in-person interviews.

Photo essay by Sydney Rinehart

.

Probing the social context of violence

Using data to call attention to broadly held misconceptions with grave, wide-reaching implications has always been a major motivator for Lori Post, PhD, director of the Buehler Center for Health Policy and Economics.

An epidemiologist who has been studying vulnerable populations and the social context of violence for decades, Post has recently been widely quoted by media outlets including The New York Times, Chicago Tribune, and CNN, in the wake of the tragic mass shootings in Texas and Ohio. Debunking the idea that these shootings are perpetrated by the mentally ill has been one of her primary focuses.

“Only about four percent of mass shootings are carried out by people with mental illness, and yet that is one of the most common narratives among legislators in Washington,” says Post, who is also a professor of Emergency Medicine and of Medical Social Sciences.

After delving into the data surrounding 98 mass shooting in the U.S. since 1982, Post found that 95 percent of mass shooters were male; they were generally young and overwhelmingly white, and 81 percent used semi-automatic weapons. And, each mass shooting was the product of careful forethought — methodic planning of each detail over the course of weeks and even years.

“There are many falsehoods about gun massacres, especially that people who perpetrate massacres have mental health problems, when in fact, massacres require so much organization that an individual with mental health issues is less likely to be able to develop and execute such a plan,” Post says.

“As Americans, if we want to make mass shootings stop, we all need to be involved in stopping hate speech, calling it out when it is said or posted on social media, and notifying the police when threats or plans of violence are named, because once an individual has developed a massacre plan, they are extremely dangerous.”

Post is also drawing attention to the fact that discussions of gun violence are missing a key component: unreported incidents. According to Post, there really are no accurate numbers on the prevalence of gun shootings in the U.S. She recently co-authored a study in The Journal of Behavioral Medicine underscoring the fact that not all incidences of gun violence are reported to the police. Moreover, no single source can possibly account for all gun shootings. The study was part of a special issue dedicated to gun violence, created in response to the National Rifle Association’s tweet telling physicians who speak out about gun violence to “stay in their lane,” a comment that Post and her colleagues across U.S. universities saw as a call to action.

“To get accurate data on gun violence, we need to consider several data sources, such as paramedic services, emergency departments, medical examiners, police records, and even media reports,” she says.

To get accurate data on gun violence,

Lori Post, PhD

we need to consider several data sources.

It is this kind of big-picture, accurate data that lawmakers need in order to make sound public health policy, and Post believes firmly in the power of academic scholars to provide it. As the director of the Buehler Center, she mentors other Northwestern investigators who want to explore how their research can inform policy decisions as well. The Center provides everything from assistance with designing studies to identifying funding sources to conducting cost-benefit analyses, empowering investigators to put science in front of decision-makers.

“Lawmakers often create policy behind closed doors without evidence,” she says, “And the question is, ‘Why not use science to inform policy?’”

Kristin Samuelson contributed to this story.