Charting a New Course

by EMILY AYSHFORD | photography by KIM BECKER

New vice dean for education, Marianne

Green, MD, has big plans for Feinberg’s

curriculum.

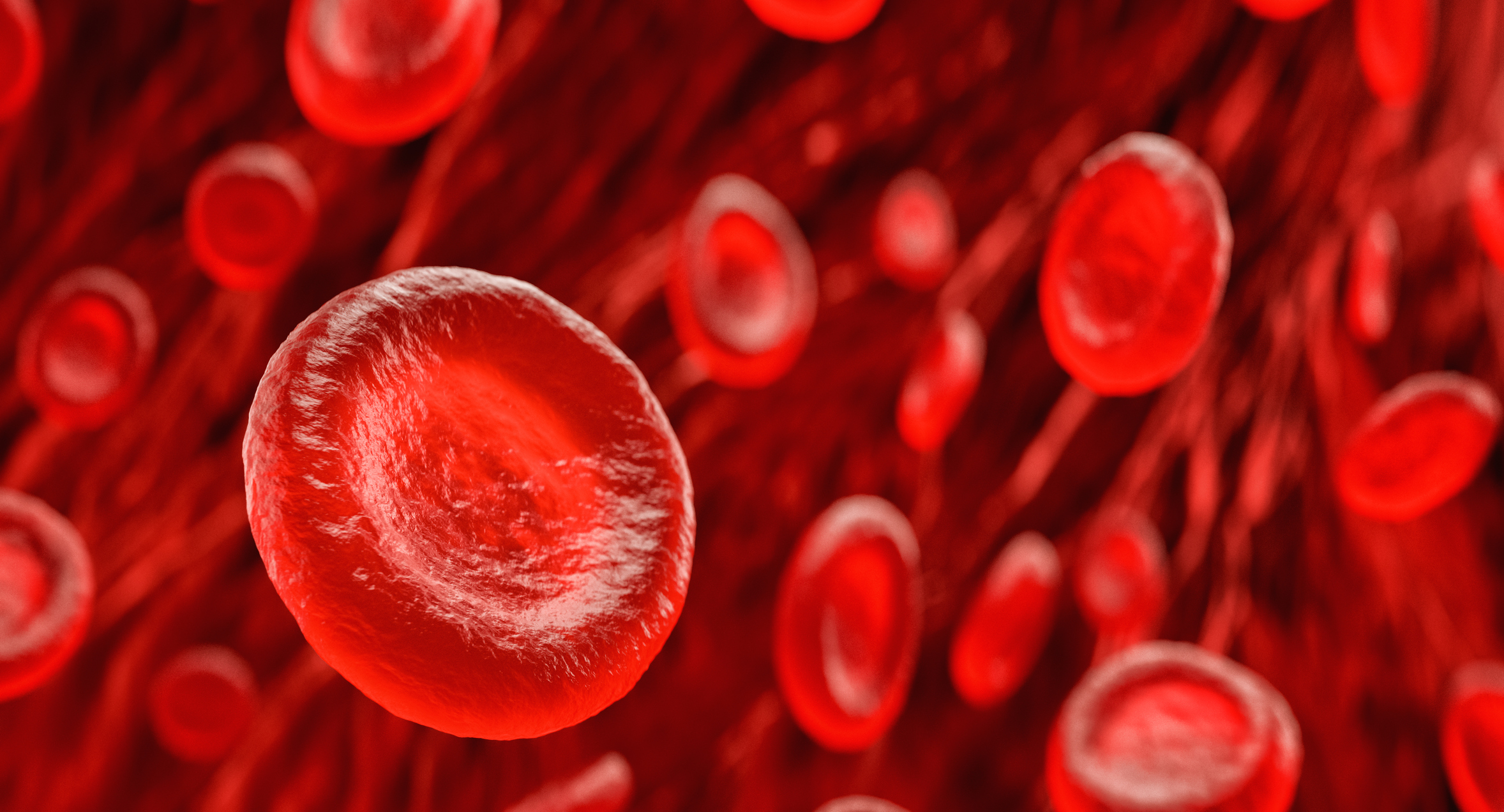

When Marianne Green, MD, was young, her father, a biochemistry professor, took her to a colleague’s lab. On a table was an anesthetized frog. Peering through a microscope at the web of the frog’s foot, she was able to see the stream of red blood cells traversing the capillaries and arteries.

“I thought, ‘This is the coolest thing ever,’” she says. Her fascination with human physiology and pathophysiology was born, ultimately leading her to medical school at the University of Illinois at Chicago School of Medicine. She found that her curiosity was most often satisfied in the specialty of internal medicine, but she could not commit to one sub-specialty. “I’m interested in too many organ systems to devote my career to only one,” she says. “In primary care, you may see a patient with autoimmune disease one moment and an ankle sprain the next. It is never boring, and I am always learning.”

The desire to share her curiosity with the next generation of physicians ultimately propelled her to a career in medical education at Feinberg, where she has received more than a dozen teaching awards while innovating the school’s curriculum. After serving in several leadership roles, she has now been appointed vice dean for education, chair of the Department of Medical Education, and president of McGaw Medical Center. In her new role, Green, the Raymond H. Curry, MD, Professor of Medical Education and of Medicine in the Division of General Internal Medicine and Geriatrics, hopes to take her educational passion — assessment — to continue to steer Feinberg’s curriculum into the future.

THE POWER OF ASSESSMENT

Green didn’t always have her sights set on education. After a residency in internal medicine at Beth Israel Hospital at Harvard Medical School, she went into private practice. But a move to Chicago in 1997 had her reconsider the direction of her career. “I realized how much I wanted to share my love of medicine with the next generation,” she says. “And that’s where I really found my stride.”

She joined Feinberg as an instructor and found her passion when she became the primary care clerkship director. As an administrator, she could reach even more students by putting new programs into place. She developed Feinberg’s first clerkship-associated objective structured clinical examination (OSCE) and realized that she didn’t want the exam to be graded. “I wanted to create a learning environment that allows students to make mistakes without fear of consequences,” she says. “The most powerful learning occurs when you make mistakes.”

In developing the exam, she began to think about the power of assessment — how feedback and learning were intimately integrated. Shortly after arriving at Feinberg, she had a personal encounter with her own assessment. She participated in a clinical communications study, where her visits with patients were recorded and assessed. “I thought of myself as a pretty good doctor with excellent patient interactions, and I received a report afterward that showed how little time I spent asking the patient if they had questions or sharing the side effects of medications,” she says. “It was so eye-opening and powerful, and I changed my practice. That’s the kind of learning environment I want to create for students — an environment where each one of them welcomes feedback that will make them a better physician.”

When she became associate dean for medical education and competency achievement, medical schools were just beginning to move toward competency-based education approaches. She led the process — which included inputs from students, residents, faculty, nurses, and social workers — to ultimately define what Feinberg’s competencies should be. She also designed the electronic assessment portfolio to review longitudinal student performance. When she developed it, she again thought back to that clinical communications study that showed her where she needed to be better. “Students need to know when they are going in the right direction and when they are going off course, and this assessment system gave students the opportunity to look at their feedback and performance over time,” she says. “It’s an opportunity for students to engage and be reflective in their own learning.”

Along the way, she continued to teach, garnering more than a dozen awards, including the Association of American Medical Colleges Alpha Omega Alpha Robert J. Glaser Distinguished Teacher Award.

Driving the Future of Medical Education

In her new role, Green has several goals. First, she is committed to creating a learning environment that allows people from all backgrounds to succeed. “We need to increase the diversity of our physician population to reflect the patients that seek our help,” she says. “While efforts at increasing the pipeline by expanding STEM programming in early education are critical, so too are the experiences that these students have while in medical school.” The medical school has recently released its commitment to social justice report, and Green is excited to help implement these efforts.

Other goals include encouraging more opportunities for interdisciplinary education. Medicine, she says, is practiced in teams, and physicians need to know how to interact and work with nurses, physical therapists, social workers, and pharmacists to provide the best holistic care for patients. She also hopes to expand community partnerships so students can better understand how social determinants — such as access to food and neighborhood safety — can negatively affect health. “Emotion drives learning,” she says. “Teaching social determinants in a classroom is not effective. They need to see it firsthand.”

Green was also recently named the co-director of the Center for Medical Education in Data Science and Digital Health within the Institute for Artificial Intelligence in Medicine, where she hopes to help create a curriculum that will give students a foundational understanding of machine learning, data science, and the application of augmented intelligence in clinical care. “Everyone who receives an MD now needs to be able to make sense of the massive amounts of data they will have at their fingertips and how to best use the rapidly evolving decision-making tools to provide the best ethical care for the patient going forward,” she says.

Amid all these goals, Green likes to relax by spending time with her three adult daughters — often dancing to reggae in the kitchen while they cook together. The youngest will attend Feinberg beginning this summer, joining the legions of students who have benefited from Green’s innovative curriculum. “I always tell my students that my job is to make them a better doctor than I am,” she says. “And that is very rewarding.”