by CHERYL SOOHOO | photography by KIM BECKER

Northwestern Medicine leads the development of a revolutionary cardiac procedure.

What could retired insurance broker Robert Salata of Libertyville, Illinois, possibly have in common with Mick Jagger? Well, not much, except for a novel cardiac procedure that allowed both men to avoid open heart surgery and dance to their hearts’ content just weeks later.

On March 30, 2019, the Rolling Stones postponed their North American tour: Jagger needed “medical treatment.” Soon after, he underwent transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) at a New York City hospital, and by May 15, a viral video showed the 75-year-old flaunting his familiar moves.

Around the same time, Northwestern Medicine patient Robert Salata, 82, was preparing himself to undergo TAVR. He had discovered in February 2019 that in addition to blocked arteries, a defective aortic valve was contributing to his shortness of breath and lack of energy. In late April, the father of three and grandfather of eight underwent coronary angioplasty to widen his narrowed arteries: Five stents were used to improve blood flow through his overworked and weakened heart. Unfortunately, an infection landed him in Northwestern Memorial Hospital’s ICU for 14 days in early May. Although he was able to regain some strength by June, Salata’s overall condition put him at high to intermediate risk for open heart surgery to repair his aortic valve. TAVR was his best option.

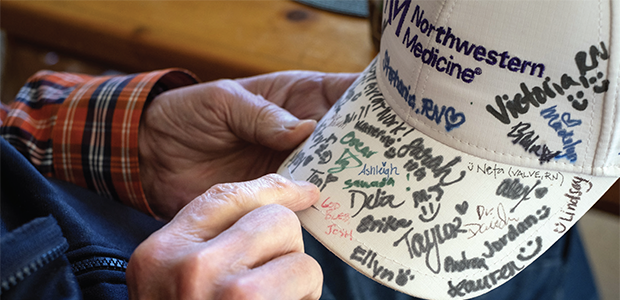

“I don’t think I would be here today without it,” says Salata, who underwent the procedure at Northwestern Memorial Hospital on June 20, a day before the Rolling Stones performed their first concert since Jagger’s treatment. By August, Salata was dancing at his granddaughter’s wedding.

We don’t stop the heart like in openheart surgery. The procedure has revolutionized the treatment of a life-threatening disease.

Charles Davidson, MD, ’85 GME

Proving a Hypothesis

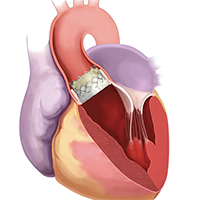

With shorter recovery times and lower complications rates than surgery, TAVR is the first procedure to offer patients with severe aortic stenosis a revolutionary alternative to cracking open their chest to reach their heart. Initially approved for frail or ill patients who may not fare well during or after valve replacement surgery, TAVR now has been proven to be superior to open heart surgery for all patients with severe aortic stenosis.

In 2008, Northwestern’s Bluhm Cardiovascular Institute became one of the first programs in the country to adopt TAVR as part of the Placement of AoRTic TraNscathetER Valve Trial of the Edwards SAPIEN Transcatheter Heart Valve or, for short, the PARTNER 1 trial. The inaugural multicenter study evaluated the safety and efficacy of the catheter-based device — an artificial heart valve made of cow heart lining tissue — in patients who were either inoperable or at high risk of surgical complications. Northwestern then participated in the PARTNER 2 trial that examined the procedure’s efficacy and ability to improve outcomes in intermediate-risk individuals. In 2016, PARTNER 3 was launched to study the benefit of TAVR for lowrisk patients. Now, three PARTNER trials later, TAVR is FDA-approved for all risk groups and is being heralded as a game changer for the approximately 200,000 patients a year who suffer from severe aortic stenosis.

In March, groundbreaking results from the PARTNER 3 trial appeared in The New England Journal of Medicine. Findings from 71 participating centers revealed that low-risk patients benefit significantly from TAVR and that their outcomes were superior or at least the same as surgical aortic valve replacement. The rates of death, stroke, re-hospitalization, major bleeding, and new atrial fibrillation at one year were significantly lower with TAVR than surgery.

“This breakthrough opens the door to many more — if not most — patients being considered for treatment with TAVR,” says co-author S. Chris Malaisrie, MD, co-chair of the PARTNER 3 national case review board and professor of Surgery in the Division of Cardiac Surgery at Feinberg. “All three studies successfully proved the hypothesis: TAVR is not inferior to surgery.”

Game Changer

Transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) is a game changer for hundreds of thousands of people who suffer from severe aortic stenosis.

Team Approach

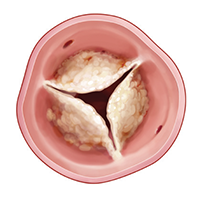

One of four valves in the heart, the leaflets of the aortic valve open and close with every heartbeat to allow oxygen-rich blood to flow to the rest of the body. A malfunctioning aortic valve can disrupt this vital circulation of blood. Aortic valve stenosis arises when the leaflets of the valve become calcified and fail to open completely. This situation leaves a narrow opening for blood to flow through, which consequently forces the heart to work harder to pump blood to adequately sustain bodily functions. Symptoms of aortic stenosis include shortness of breath, chest pain, passing out, and even death. The incidence of aortic valve stenosis increases with age and can appear in patients in their 60s, 70s, and 80s.

Medication can help to manage symptoms for mild and moderate cases of aortic valve disease. However, severe aortic stenosis with symptoms demands mechanical intervention: It is associated with approximately 50 percent mortality at one year without valve replacement. Previously, patients with severe stenosis faced open heart surgery for their valve replacement in an operating room. Now, more likely than not, patients will undergo TAVR in the Cardiac Catherization Lab.

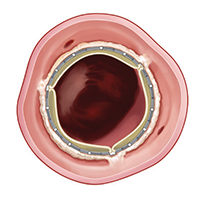

An interventional cardiologist and a cardiac surgeon jointly perform the novel 30- to 60-minute procedure, with the patient generally requiring only moderate sedation. The valve used in TAVR is mounted on a stent and is compressed on a balloon catheter or tube-like device. One specialist positions the artificial valve by inserting the catheter in through the patient’s groin and across the blocked heart valve. The other operator deploys the device by expanding the balloon, which anchors the replacement valve to the diseased aortic valve. Unlike surgical replacement where the “native” valve is entirely removed and replaced, with TAVR the diseased valve is just pushed aside by the new valve.

During TAVR, the clinical team lowers the patient’s blood pressure by increasing the heart rate for the 10 to 15 seconds it takes to properly deploy the new valve. “That’s another one of the advantages of TAVR,” says Charles Davidson, MD, ’85 GME, vice chair for Clinical Affairs, clinical chief of Cardiology, and professor of Medicine at Feinberg. “We don’t stop the heart like in open-heart surgery. The procedure has revolutionized the treatment of a life-threatening disease by lowering the procedural risk, shortening recovery times, and extending the lives of our patients.”

The presence of a cardiac surgeon ensures that if complications should arise during TAVR, the heart valve team can immediately take the patient to surgery. A rare occurrence hovering around 1 percent or less, surgery is required about two times a year for the 230 procedures performed annually at Northwestern Memorial Hospital, according to Malaisrie.

One of the nation’s top 10 enrollment sites for PARTNER 3, Northwestern Medicine has led the development of this treatment option since TAVR’s introduction. The academic medical center system currently offers TAVR at Northwestern Memorial, and in the suburbs of Chicago, at Central DuPage Hospital and McHenry Hospital. At Northwestern Memorial Hospital, the heart valve team has three cardiac surgeons and four interventional cardiologists — among them Davidson’s daughter Laura Davidson, ’11 MD,’18 MS, ’18 GME — experienced with performing TAVR.

It’s gratifying for us to have played such a significant role in providing treatment options that otherwise, until recently, would not have been available.

S. Chris Malaisrie, MD

A Life-Altering Procedure

Northwestern Medicine’s depth and breadth of experience with TAVR brought Morton Grove, Illinois, resident Donald Weiss to Northwestern Memorial Hospital last summer. The Chicago Public Schools special education teacher quickly learned he needed a new aortic valve when he was left speechless and panting trying to catch his breath while walking in an airport. His friend, a retired physician who had undergone TAVR, had said Northwestern Medicine was the place to go. Meeting the criteria for being at low-surgical risk with relatively good health, Weiss, 74, was a candidate for the PARTNER 3 trial.

“They had to tell me about the risks of TAVR such as major bleeding or a stroke but I said, ‘Do it the easy way. You are not opening up my chest,’” recalls Weiss, who had the procedure in September. “I was out of the hospital in three days and was back to my normal activities within a month. There were no other options for me!”

Fortunately, more and more patients like Weiss and Salata with severe aortic stenosis do have options thanks to TAVR. And their loved ones are grateful for it and the stateof- the-art care they received at Northwestern Medicine. “Between TAVR and the other advanced cardiac care my dad received, it truly is a miracle he is here with us today,” says Salata’s son, Bob Salata, Jr.

Salata’s daughter Amy Shanahan agrees wholeheartedly and greatly appreciates the many more wonderful memories — from fishing trips to a granddaughter’s wedding — her father has shared with his family since his TAVR procedure. “We are so happy to have our dad to celebrate with us,” she says.

Moving forward, Northwestern Medicine investigators and others are studying TAVR for use in asymptomatic patients — individuals who have severe aortic valve stenosis but haven’t yet exhibited debilitating symptoms. The goal is to further broaden the benefits of TAVR.

“This is truly a life-changing and lifesaving procedure,” says Malaisrie, who has served as site surgical principal investigator (PI) for all three PARTNER trials at Northwestern, with Davidson serving as site interventional cardiology PI. “It’s gratifying for us to have played such a significant role in providing treatment options that otherwise, until recently, would not have been available.”