by ED FINKEL | photography by EILEEN MOLONY

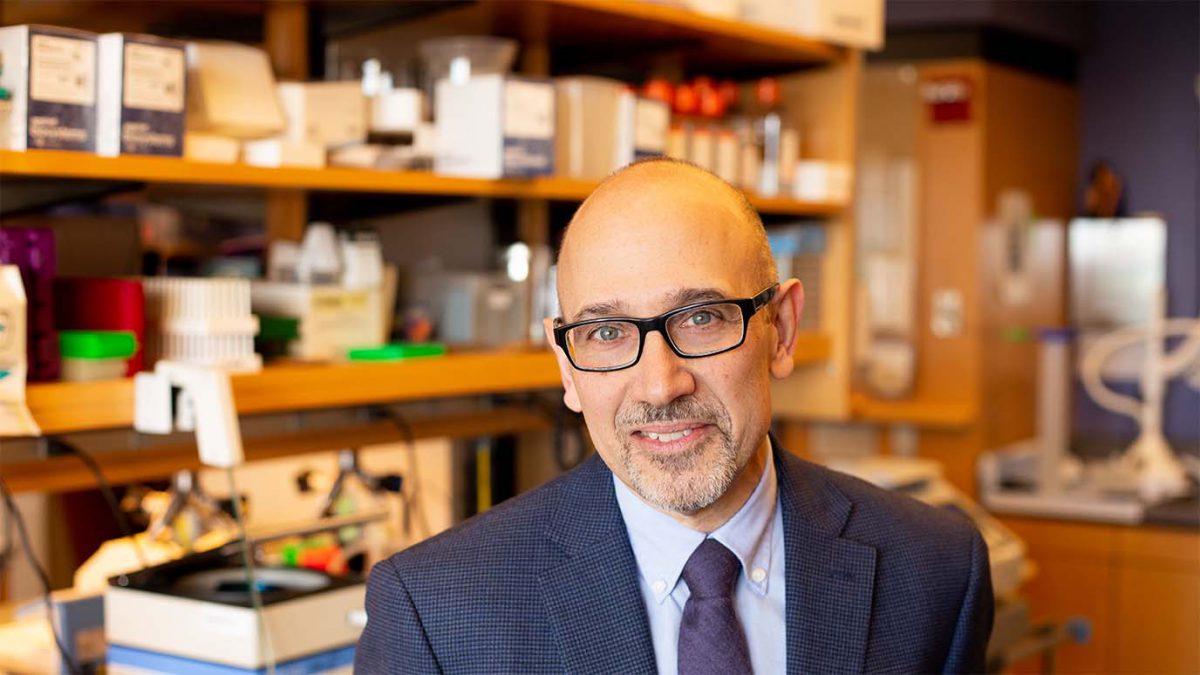

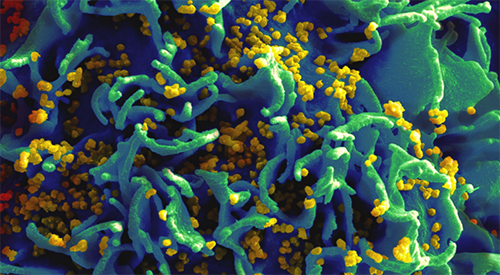

This past summer, as Richard D’Aquila, MD, was assuming his new role of director of the Northwestern University Clinical and Translational Sciences (NUCATS) Institute, scientists across Northwestern and around the world were in the midst of responding to the COVID-19 pandemic. A professor of Medicine in the Division of Infectious Diseases, D’Aquila is no stranger to a pandemic — albeit a different one. He has spent the past 35 years contributing to the advances in medicines for HIV infection and their personalization, which have led to AIDS becoming much less common.

While gratified by the advances in treatments that improve longevity for patients with HIV, when taken for the rest of their lives, D’Aquila says that a cure would greatly improve patients’ quality of life and their lifespan. “People who have HIV that is well treated with these medicines still have so much overactive immunity and systemic inflammation that they get conditions associated with aging — including heart disease, strokes, kidney disease, liver disease, and mild cognitive decline — at least 10 or 15 years earlier,” he says.

He also cites another obstacle to ending that other, still-problematic pandemic: “Disparities in both prevention and care for HIV persist and help the virus spread,” he says.

In his new position, D’Aquila, who is also a member of the Robert H. Lurie Comprehensive Cancer Center of Northwestern University, is uniquely qualified to both continue his prolific HIV/AIDS research and, at the same time, shepherd NUCATS during this crucial moment in scientific discovery.

“It’s interesting to take on this new position at this point in time, given the social and medical challenges facing us today. Our NUCATS team is working hard to do more to improve equity of health and healthcare, as well as accelerating new advances in prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of diseases — including COVID-19,” says D’Aquila, who is also associate vice president of research, senior associate dean for Clinical and Translational Research, and the Howard Taylor Ricketts, MD, Professor.

People who have HIV that is well treated still have so much overactive immunity and systemic inflammation that they get conditions associated with aging — including heart disease, strokes, kidney disease, liver disease, and mild cognitive decline — at least 10 or 15 years earlier.

An early interest in HIV/AIDS

After earning an MD from Albert Einstein College, D’Aquila began to focus on HIV/AIDS research during his internal medicine residency at University of Pennsylvania. In 1982, for a one-month research elective, he and his mentor were among the first to study the then-newly identified disease, before its viral cause was discovered. After starting research on another virus during a fellowship that followed at Yale University School of Medicine, D’Aquila pivoted to working on the virus causing AIDS immediately after it was identified. His work moved to Massachusetts General Hospital, where he focused on developing treatments and diagnostics to guide their use in the laboratory and in clinical trials. He began leading interdisciplinary scientific teams, and this work took full flight once he became the Addison B. Scoville, Jr., Professor of Medicine at Vanderbilt University, as well as chief of infectious diseases and director of the Vanderbilt AIDS Center.

D’Aquila pursued the research track because as a clinician in the mid-to-late 1980s, he was treating so many dying patients. By the early 1990s, HIV was the number one cause of death among Americans ages 25 to 44. Promising early single-drug treatments such as AZT became less effective as the virus mutated. Research was where he felt he could make the most difference.

“What led to real advances was basic science and understanding the structures of viral proteins in order to design and perfect new drugs,” says D’Aquila.

D’Aquila contributed to laboratory research on combining anti-HIV medicines and then led multi-center clinical trials of new combinations, including some of the first medicines specifically designed through basic science to inhibit HIV proteins. He also focused on developing assays to identify HIV resistance to specific anti-HIV medicines and led a nationwide collaborative group designing and running clinical trials to prove their usefulness.

By the 2010s, viral resistance became less common, with improved antiretroviral therapy (ART) allowing people with AIDS to lead fuller lives. This led D’Aquila and others to shift their focus to figuring out how to achieve a sustained remission, even after stopping antivirals — in other words, how the body could fight off the disease on its own.

“ART does not cure HIV,” says D’Aquila. “If it’s stopped at any time, the HIV infection rebounds within three weeks from a small number of cells where it persists in the body during treatment.” Additionally, notes D’Aquila, “Medicines are expensive, there are side effects, and you have to take them every day for the rest of your life.”

Bringing more HIV/AIDS research muscle to Feinberg

The HIV/AIDS research enterprise at Feinberg is substantial, and in 2015, D’Aquila was instrumental in helping it grow with the founding of the Third Coast Center for AIDS Research (CFAR), a partnership between Northwestern University and other Chicago-based universities, health departments, clinics, and community organizations that have helped sustain that research growth and strengthened collaborations.

Today, a significant research focus in the D’Aquila lab is on discovering how a future medicine might boost defensive immune system proteins called APOBEC3s (or A3s for short) to achieve sustained remission after ART stops or, even more optimistically, a cure. He and his colleagues discovered that more ample stores of cellular A3 appear to be a part of what very rarely enables HIV-infected individuals to control the virus naturally — without antiviral drugs. Published in PLOS ONE, this finding has important implications.

A second, complementary strain of D’Aquila’s research, published in PLOS Pathogens, AIDS, and Cell Reports, has been examining the T-cells that the HIV virus infects and sometimes replicates itself from, trying to figure out why the virus is only able to replicate from activated, and not resting, T-cells. This could help develop inhibitors that would block HIV replication, increasing cells’ resistance to the incoming virus and perhaps also decreasing the reactivation of persisting and latent viruses, D’Aquila explains.

“Putting those things together might get us to a place where we can stop antiretroviral medicines for months or even years, and maybe longer,” he says. “But even stopping them temporarily would be a huge advance and give us clues for research on how to prolong such success.”

We do a lot to engage community organizations in our research, bring them in as stakeholders, and listen to what they say in terms of how we’re doing research, and what research is of value to the community. We need to do even more.

Leading on multiple fronts

In the three years before his new appointment, D’Aquila assumed a broader leadership profile at Feinberg as associate director of NUCATS and director of its Center for Clinical Research (CCR).

“I’m most proud of CCR’s collaborations with Northwestern Medicine on the Clinical Research Unit, and with many investigative teams around multicenter studies and resources of the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) Trial Investigation Network,” he says. “We’ve been leading a lot of cutting-edge discoveries and moving new medicine into clinical practice. There’s a lot that we still need to learn, though, about how to implement our successful new therapeutic and preventative advances, so they reach all the people who need them.”

As D’Aquila transitioned into his new role at NUCATS, the institute also played a key role in Feinberg’s mobilization surrounding COVID-19. Since the pandemic began, NUCATS has awarded investigators pilot grants, many of which have seeded new NIH grant applications and collaborations. NUCATS CCR also helped on a task force created by Eric G. Neilson MD, vice president for Medical Affairs and the Lewis Landsberg Dean, which is aimed at prioritizing and coordinating COVID-19 research efforts by answering researchers’ questions about the feasibility of their ideas and helping to identify potential collaborators. D’Aquila is also part of the team of Northwestern investigators conducting the Screening for Coronavirus Antibodies across Neighborhoods (SCAN) study to better understand how individuals, households, and Chicago neighborhoods have been exposed to COVID-19, including examining the virus’s disproportionate impact on Black

and Latinx communities.

“Racial justice, racial inequity, structural racism — all of those topics are front and center for NUCATS,” D’Aquila says. “We do a lot to engage community organizations in our research, bring them in as stakeholders, and listen to what they say in terms of how we’re doing research, and what research is of value to the community. We need to do even more.”

Outside of work, D’Aquila takes great pride in the educational progress of his daughter, a second-year student at Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine. While he’s mostly staying at home and working these days, once a vaccine for COVID-19 is found, he looks forward to returning to other passions. “I want to get back to our fabulous restaurant, theater, and music scene in Chicago,” he says. “I love going to jazz and blues venues. Someday soon, we will do that again.”