Science in Practice

Northwestern Medicine scientists are ensuring that evidence-based practices are put to use properly.

by Bridget M. Kuehn

It can take close to 20 years for evidence from clinical trials to make its way into practice in the U.S. But an emerging field called implementation science is aiming to change that.

“Implementation science emerged because many physicians and scientists realized that we should not be satisfied with the years it can take for evidence-based therapies to find their way into everyday practice,” says Tara Lagu, MD, MPH, who last spring was named director of the Center for Health Services and Outcomes at Northwestern’s Institute for Public Health and Medicine (IPHAM). “We want to accelerate both the dissemination and implementation of evidence.”

Lagu, who is also a professor of Hospital Medicine, is part of a growing cohort of scientists at Northwestern who are doing just that.

“Implementation science aims to systematically identify barriers and facilitators to the use of evidence-based practices in the real world, and to design and rigorously test implementation strategies that ensure every patient — no matter who they are or where they are — gets the best care possible,” she says.

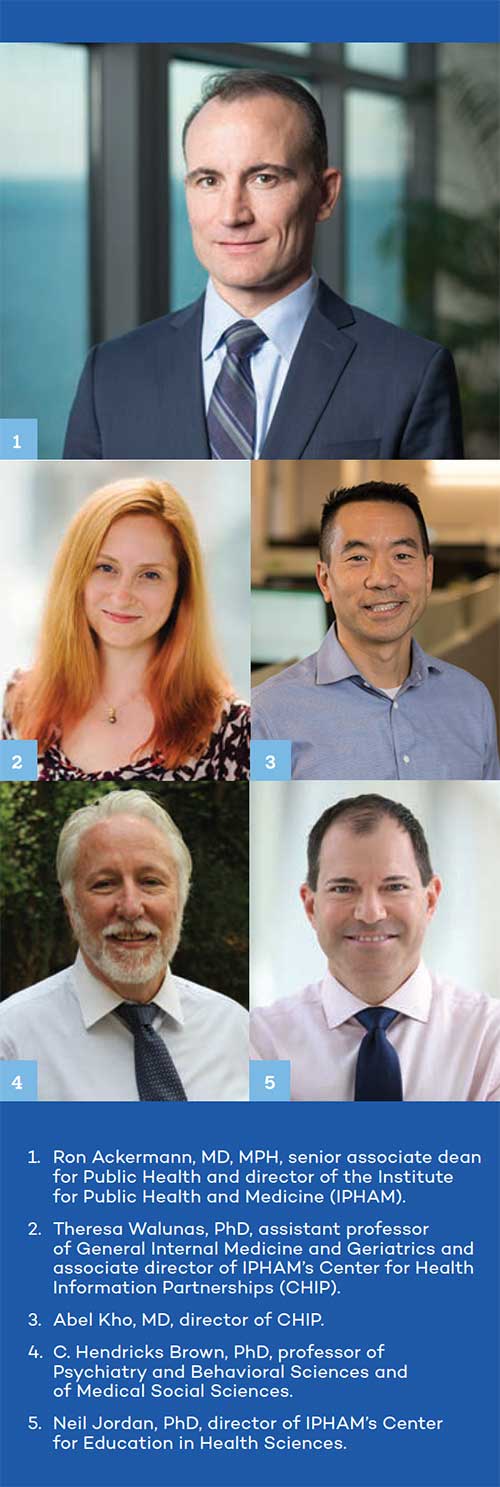

“There are several research studies in motion right now at Northwestern that are designed to examine whether a new treatment approach is effective, while also studying how routinely and sustainably it can be delivered in Northwestern Medicine practice settings or Chicago communities,” adds Ron Ackermann, MD, MPH, senior associate dean for Public Health and director of IPHAM. “This is definitely a growth area for us.”

‘Uniquely Positioned’

The field has taken on new urgency this year as the COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated serious health disparities, and according to Lagu, Northwestern is uniquely positioned to be a leader. She explains that Northwestern Medicine has “a learning health system model,” which is made up of a growing cohort of multi-disciplinary experts in implementation science and the ability to use real-world data from electronic health records. The health system also has long-standing community and multi-institution partnerships. Additionally, there is a commitment to building the infrastructure necessary to support large-scale research that simultaneously evaluates both effectiveness and implementation of promising new interventions.

“Northwestern is one of the few places in the United States that has the opportunity to incorporate the principles of implementation science into health services and outcomes research, healthcare delivery, quality improvement, community-based participatory research, and community-led health interventions,” she says. “That’s a big part of what drew me here.”

Currently, Lagu is the principal investigator on two R01 grants from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute focused on heart failure. One of those grants aims to identify implementation strategies that increase the use of cardiac rehabilitation among patients with heart failure.

She and her colleagues are working to identify unique barriers to cardiac rehabilitation (CR) among patients with heart failure, ranging from patient-level barriers, such as poor physical condition and lack of transportation, to health system barriers, such as difficulty identifying and recruiting eligible patients. The investigators are in the process of conducting interviews with hospitals and practices that have successfully increased uptake of CR among patients with heart failure. This work will identify strategies that overcome barriers to attendance. Eventually, they plan to test the strategies that seem feasible and acceptable to patients, physicians, practices, and health systems. Her work was inspired by personal experience.

“I saw first-hand that cardiac rehabilitation improved my father’s quality of life,” she says. “He suffered from heart failure and, in 2014, was so ill and deconditioned that I thought he only had months to live. Instead, he attended CR, and although he passed away in January 2021, his quality of life in his last five years was greatly improved. The exercise training provided by CR has been demonstrated, in clinical trials, to improve quality of life and reduce hospitalizations among patients with heart failure. Yet our early work suggests that less than 10 percent of eligible patients with heart failure ever attend even a single session of CR. When I saw the data, it was clear: the slow uptake of CR is a classic implementation science problem.”

Practical Solutions

Often, the challenges to implementing new therapies or interventions in practice are practical ones. New

medications and therapies are far more costly than existing options, and there may be considerable costs for a practice or hospital to implement a new intervention, explains Neil Jordan, PhD, director of IPHAM’s Center for Education in Health Sciences.

For example, clinicians may need training, or modifications may need to be made to electronic medical records. Jordan specializes in analyzing both the cost-effectiveness of a new intervention and the implementation costs of putting it into practice.

“The results from those analyses are really essential to making the business case for a clinic, provider, hospital, or health system — or whoever it is that’s going to adopt a new intervention,” says Jordan, who is also a professor of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences and of Preventive Medicine.

Often interventions that are tested and shown to work in academic medical centers require significant adaptation to be used effectively in real-world healthcare settings that often have fewer resources for implementing new care strategies. Professionals known as “practice facilitators,” who have backgrounds in health information technology, can help provide coaching to health system leaders and clinicians on how to adapt an intervention to their setting and use their electronic health record system to improve care processes and measure patient outcomes, says Theresa Walunas, PhD, assistant professor of General Internal Medicine and Geriatrics and associate director of IPHAM’s Center for Health Information Partnerships (CHIP). They also help assess which real-world adaptations are most effective and how coaches can be the most effective.

“We are not developing new interventions,” Walunas says. “What we are doing is saying: ‘It is great that you can do this in a highly tooled academic medical center, but what really matters is how does it fare in a more real-world setting of small practices?’”

Along these lines, Walunas and investigator Abel Kho, MD, director of CHIP, collaborated to develop an implementation model comprising a bundle of implementation strategies to improve the use of evidence-based cardiovascular disease prevention in primary care clinics in Wisconsin, Illinois, and Indiana, through a program called Healthy Hearts in the Heartland. Now, Walunas is helping to lead a project that will apply that model in rural Michigan practices through a program called Healthy Hearts for Michigan.

In addition, the two are also collaborating on adapting this practice implementation model developed as part of the Healthy Hearts program to an area of behavioral health, with the goal of increasing the uptake of evidence-based screening and brief interventions in primary care for unhealthy alcohol use.

“As the pandemic has gone on, people have realized alcohol use disorder is becoming more and more of a problem,” says Kho, who is also director of the Institute for Artificial Intelligence in Medicine and professor of Medicine and of Preventive Medicine. “It’s very timely.”

Community-Led

Northwestern’s scientists are also lending their expertise to support community-led health interventions. Northwestern provides support to Pastors 4 PCOR (P4P), which was launched in 2014 by faith leaders in Chicago in partnership with the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research (PCOR) Institute. The P4P program trains faith-based community facilitators to lead research programs designed to meet needs in their communities. One identified need is for better blood-pressure control.

“We changed the paradigm by getting to the table with the researchers,” says Paris Davis, MBA, PhD, co-leader of P4P and executive director of P4P and the Total Resource Community Development Organization (TRCDO) at Triedstone Church of Chicago. Davis has run TRCDO, a one-stop, comprehensive social services agency, for more than 20 years and has become intimately familiar with the community’s needs and the best ways to reach subsets of people within it. Now, she’s using that expertise as co-PI of one of Northwestern’s newest implementation science projects, the Community Intervention to Reduce Cardiovascular Disease in Chicago (CIRCL).

Davis is working with Kho and J.D. Smith, PhD, a former associate professor of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences and current adjunct associate professor at Northwestern who recently joined the faculty at the University of Utah. The program will apply a blood pressure management implementation model developed by Kaiser Permanente within multiple faith-based settings. The CIRCL team aims to improve blood pressure management for diverse community residents by evaluating implementation strategies that expand access to blood pressure monitoring at home or in faith-based settings, according to Kho.

“We are super excited about CIRCL because it is the culmination of collaborations we’ve built for many years,” he says.

Range of Stakeholders

While there is an overlap between community-engaged research and implementation science, implementation projects have stakeholders spanning multiple areas.

“One cannot design useful implementation strategies for delivering an effective treatment or support service in a real-world setting if one does not consider and involve ‘the user,’ or the people delivering the intervention — and often, this is a community,” Ackermann says. “However, a stakeholder in implementation science can range from an individual doctor to a practice to a policy agency.”

One such stakeholder is the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, which is partnering with the Chicago Department of Public Health and Northwestern for its Ending the HIV Epidemic initiative, aimed at reducing the number of new HIV infections in the United States by at least 90 percent by 2030. The Chicago-based efforts are being led by C. Hendricks Brown, PhD, professor of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences and of Medical Social Sciences.

Brown, who is one of the leading founders of the field of implementation science, and his colleagues are using computer simulations to help the Chicago Department of Public Health find the best strategies to quickly scale up the administration of antiretroviral therapies (ART) and pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) in the city. It will focus on two high risk groups: young men who have sex with men and African American and Latino men who have sex with men.

“We know right now the levels of ART and PrEP use in the community are insufficient to end the HIV epidemic in 10 years,” says Brown, who is also director of Northwestern’s Dissemination and Implementation Program. “The simulations are support tools — they are not designed to tell CDPH or communities what to do — but they can inform them what programs could work under what circumstances, and what programs are not likely to work at all.”

Brown notes that the overall goal of implementation science, like all of healthcare, is to improve the quality of people’s lives, and that the field emphasizes the need to address a lack of health equity and systemic racism affecting communities of color.

“Northwestern has a really critical role to play in this next phase of research that takes programs to scale and delivers them to communities,” he says. “I’m proud to be a part of that.”