Reaching Further

Northwestern’s African American Transplant Access Program is impacting lives in Chicago’s most underserved communities.

by Christina Frank

Every year, Dinee Simpson, MD, assistant professor of Surgery in the Division of Organ Transplantation and the only Black female transplant surgeon at Northwestern Memorial Hospital, gets a text from the daughter of a patient who received a liver transplant through Northwestern Medicine’s African American Transplant Access Program (AATAP).

“She messages me every year on her mother’s transplant anniversary to say they are reminded of where she was at and how scary it was, and how likely she was to die if this program hadn’t been here,” says Simpson.

Simpson is the first and only Black female transplant surgeon in Illinois, and one of only 11 in the U.S. She is working to address a life-threatening situation in Black communities: distrust of the healthcare system.

“There’s a really good reason for this distrust,” says Simpson. “We have a long history in this country of the mistreatment of Black patients, as well as certain myths that get passed down within the community.”

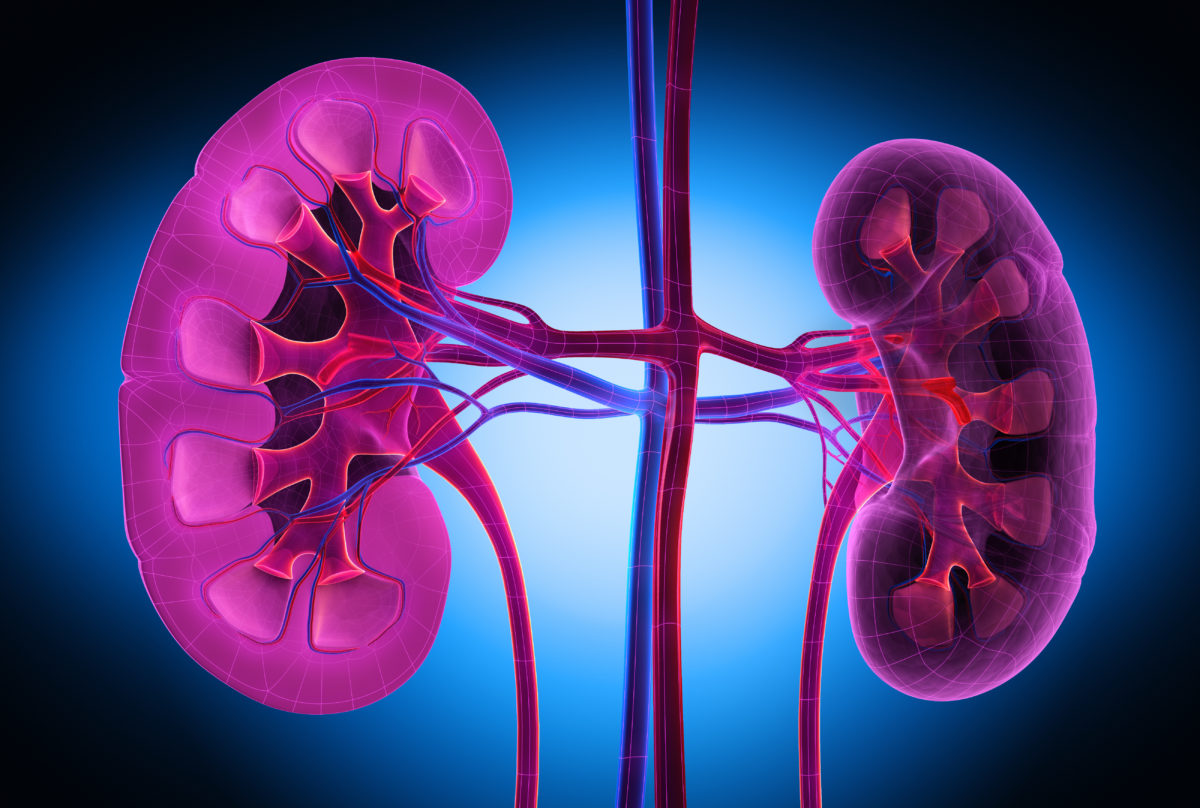

Kidney diseases in particular are a leading cause of death among African Americans. While genetics plays a role, factors like limited access to healthy food and medical specialists in underserved neighborhoods drive up the already high rates of diabetes and hypertension — both major factors in kidney disease. Black patients are about 25 percent more likely to die from liver-related disease compared to non-Hispanic white patients and four times less likely to receive a liver transplant, according to recent research done at Northwestern.

In response, Northwestern Medicine has made it a priority to address the pressing issue of health equity, in both diseases of the liver and the kidney.

“One of the most urgent national and global issues in nephrology, and medicine more generally, is health injustice,” says Susan Quaggin, MD, director of the Feinberg Cardiovascular and Renal Research Institute and chief of Nephrology and Hypertension in the Department of Medicine. “If we are to achieve kidney health equity and equal access to the best treatment for all patients, we must develop new approaches to healthcare and innovative programs led by talented and visionary leaders.”

One of the most urgent national and global issues in nephrology, and medicine more generally, is health injustice.

Susan Quaggin, MD

With these goals in mind, Northwestern recruited Simpson to develop the AATAP, aimed at addressing the needs of African Americans in underserved communities. She began building the program in 2018 and it was officially launched in 2019. Recently, Simpson hired a dedicated social worker and opened a satellite clinic in Oak Lawn, a suburb on the southwest side of Chicago.

“The location was very strategic,” she says. “It’s where Black communities tend to be clustered, but the main reason is ease of access, which is one of the barriers that communities of color face.”

Having the satellite clinic helps offset travel logistics and costs involved in coming to the downtown location. “Patients still need to come to Northwestern Memorial when it comes time for transplant and for follow-up, but for that initial intake visit it’s really been fantastic for the patients in the vicinity to go to the Oak Lawn location.”

Meeting Demand While Addressing Practical Matters

The demand for the program has been overwhelming. In just under two years, the AATAP has arranged for 14 transplants, seen a 55 percent increase in evaluations of Black patients at Northwestern, and an 18 percent increase in Black patients on the transplant waiting list. (Currently, 80 percent of patients are candidates for kidney transplants and 20 percent for liver transplants.) The team has just onboarded a health literacy coach and hopes to add more dedicated health providers eventually.

As part of a related initiative, Simpson, Northwestern University, and AATAP are partnering with the Endeleo Institute, a non-profit member organization of the Trinity United Church of Christ, focused on creating a culture of health in Chicago’s Washington Heights neighborhood. Endeleo has recently established a food pantry in the neighborhood and the project plans to add nutrition programming, support groups, and educational resources to help guide community members in making better food choices that can help improve disease, with a specific focus on kidney disease.

Bottom: Simpson in a consultation.

Navigating the many aspects of psychosocial support can also be especially daunting for Black transplant candidates. This is where AATAP’s social worker Shimere Harrington, LCSW, steps in and helps patients secure insurance coverage as well as understand and find the financial resources they need to offset the costs of immunosuppressive medications required after transplant surgery.

Another challenge is lining up in-person care once the patient is back home. A prerequisite for any organ transplant candidate to get on the waiting list is for them to identify people who can be with them 24 hours a day for anywhere from two to six weeks post-transplant. Patients in economically disadvantaged situations are often less likely to have friends or loved ones who can take time off from their jobs to help out.

Simpson had one patient who was at risk of being denied a transplant because she was unable to arrange the home care she needed. AATAP was able to patch together a non-traditional form of support by reaching out to the members of the patient’s church as well as locate resources for hired nursing care.

“It was also important to help the transplant committee reset their expectations around what we think a support network should look like,” says Simpson, who refers to this piece of AATAP’s intervention goals as “cultural competency” on the part of healthcare providers who may not be familiar with the circumstances or culture in Black communities.

Addressing a Systemic Problem

Simpson stresses that while it’s very exciting to see AATAP making a difference on a community level, this is just the tip of the iceberg. “The reason that we have a need for programs like this is because of structural and institutional issues that are at the base of the iceberg. We have a beautifully diverse city, but it’s segregated. And in these communities of color, there are few resources,” she says.

“So, we are just treating symptoms of a much larger systemic problem that needs to change. AATAP is not going to ultimately fix the problem. We need to make sure that we’re paying attention to the bigger structural issues. There needs to be some policy change. There needs to be addressing of these larger systemic issues.”

Past negative experiences with the health system may haunt some patients and contribute to their skepticism when faced with a potentially life-threating diagnosis. Originally, the patient whose daughter regularly texts Simpson on her mother’s transplant anniversary staunchly refused to consider a transplant because she was convinced it was an experimental treatment, Simpson recalls.

It was important to help the transplant committee reset their expectations around what we think a support network should look like.

Dinee Simpson, MD

“I spent hours with this woman over a number of days,” Simpson says. “And through that time, I earned her trust. There are a number of papers in the literature about studies on distrust and on patient experience. And one thing that they’ve noted is that in these situations being the same race as the provider can build trust.”

The team also prioritizes patient-centered communication in which they use layman’s terms to explain medical conditions and procedures and avoid speaking over the patient.

“We had a lot of family meetings where we came together as a group to let this woman know that her family loved her,” Simpson says. “They wanted her to be around. Everybody was scared to death at the thought of losing her.”

Thanks to the AATAP, the patient is now doing well, according to Simpson. Meanwhile, the transplant team continues to do everything they can to help others like this patient every day.

At the Forefront of Kidney Care

The Northwestern University George M. O’Brien Kidney Research Core Center (NU GoKidney), led by Quaggin, is dedicated to ensuring that potential therapeutic targets for kidney diseases are identified, tested in preclinical studies, and advanced to first-in-human clinical trials.

A major breakthrough in recent years has been the ability to grow tiny kidneys in a dish. Quaggin says such organs could be developed from human skin cells or cells from a person’s urine. Others across the world are growing such organs, but Quaggin and her team are using genome editing technology to understand and ultimately grow blood vessels for these kidneys, a missing piece of the bioengineered puzzle, which will allow the kidney to be “hooked up to the rest of the body,” Quaggin explains.

The kidney division at Northwestern has also been part of several recent clinical trials studying the kidney-protective effects of SGLT2 inhibitors (a class of prescription medicines that are FDA-approved for use with diet and exercise to protect the kidney and hearts of adults with Type 2 diabetes) in patients with and without diabetes. In fact, these therapies received breakthrough status at the FDA, which is rare, according to Quaggin.

Joseph Leventhal, MD, interim chief of Organ Transplantation in the Department of Surgery, has focused his research on eliminating the need for immunosuppressants in kidney transplant patients. The procedure, called tolerance induction, involves therapeutic cell transfer, in which stem cells from the donor are also transplanted into the recipient.

“We currently have, I think the world’s largest experience of successfully taking living donor kidney transplant recipients entirely off immunosuppression medications through the use of combined kidney and stem cell transplant for mismatched donor and recipient pairs,” he says.

This new treatment creates a situation where the new immune system does not see the organs as different, Leventhal explains. “We have been able to get close to 30 patients off immunosuppression using this approach. And we now have five patients who have been off immunosuppression for more than 10 years.”