Trailblazers in Orthopaedics

How a close-knit, multigenerational group of Black orthopaedic surgery residents put their mark on Northwestern Medicine

by Gina Bazer

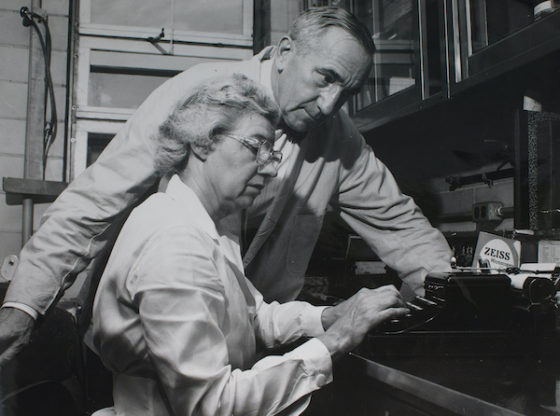

On a rainy evening in March, seven surgeons, all of whom completed their residencies at McGaw Medical Center of Northwestern University, gathered at a Streeterville restaurant to share a meal with their friends, colleagues, and mentors. Professionally speaking, they were convening for the annual meeting of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, but this intimate party was much more than a convention of people in the same specialty — it was a cherished opportunity to reconnect with kindred spirits.

Spanning more than 50 years at Northwestern, this group of six Black men and one Black woman (along with six others who were not present) have helped one another break barriers and climb ranks in what’s known as the whitest specialty in medicine: orthopaedic surgery. Trailblazers at Northwestern and in their profession alike, each of them is passing a torch to the next generation as they continue to fight for more diversity and inclusion in their chosen field, which is currently less than 2 percent Black.

Memories of Prejudice, Partnership, and Perseverance

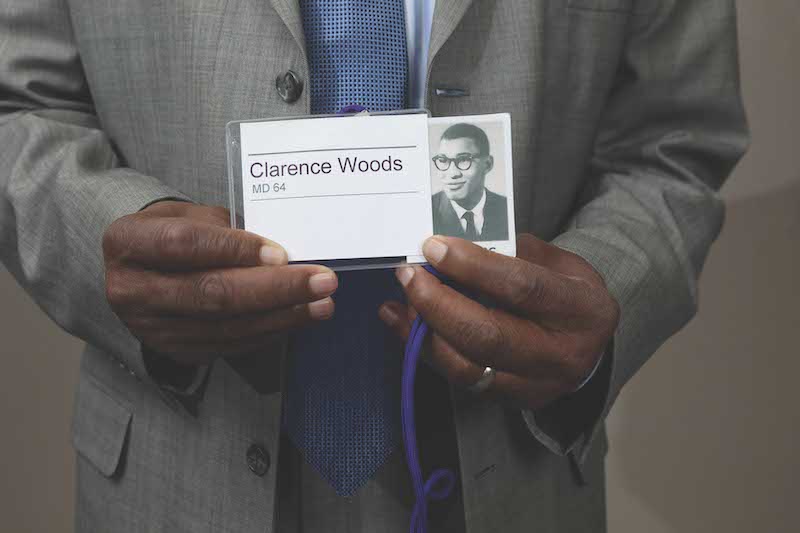

The first surgeon to enter the room was, fittingly, Clarence Woods ’64 MD ’72 GME, who in 1973 became the first Black board-certified orthopaedic surgeon in Chicago. Northwestern’s first Black resident and a celebrity in the group, he also received a Bronze Star for distinguished U.S. Army service in Vietnam from 1966 to 1967.

“There is my hero,” said Audley Mackel III, MD ’86 GME as he entered, making his way to Woods to shake his hand.

Woods retired in 2014 and lives in Sedona, Arizona, after a long, successful career as a general orthopaedic surgeon in Los Angeles. He served as chief of Orthopaedics at Martin Luther King, Jr./Drew Medical Center for 10 years, training more than 30 orthopaedic surgeons. Yet, during his time as the only Black orthopaedic resident at Northwestern, he put up with frequent indignities, including being prevented from seeing some of the white patients at Evanston Hospital.

The dinner party also included Woods’ wife Pamela Woods (seated next to Woods) and her son, Shawn Hill (seated across from Woods), along with Angela Mota from Northwestern’s office of development (to the right of Pamela Woods) and Gina Bazer, editor of Northwestern Medicine magazine (to the right of Morgan).

“My attending would say, ‘You have to understand … that’s just the way it is with some people,’” Woods recalled. “It was hard to hear that, but I also experienced plenty of support from faculty and fellow trainees.”

With his determination and undaunted spirit, Woods paved the way for others to follow, starting with Randall Morgan, Jr., MD, MBA, ’74 GME, who earned his MD degree from Howard University, a historically Black university.

Another recognized champion of equity in medicine, Morgan, too, experienced painful humiliations during his residency, such as the time a white patient at Passavant Memorial Hospital refused to allow him to treat her fractured wrist. “This patient told me to call Dr. James Stack, who was doing laps at Lake Shore Athletic Club at the time. So, I did, and I explained the situation,” he said. “Dr. Stack told me to tell this patient that if the procedure was too tough for me to do, then it was too tough for him, too, and so she finally let me do it.”

“There were other allies, too, like Dr. William Kane, Dr. Michael Schafer, and Dr. David Stulberg, and fellow residents who were truly color blind,” Morgan added. “They fought for us.”

Morgan would eventually go on to devote more than 40 years to fighting for healthcare equity. He currently serves as the founding executive director of the W. Montague Cobb/National Medical Association Health Institute. He was also the 95th president of the National Medical Association and maintained an orthopaedic surgery practice in his hometown of Gary, Indiana, before moving to Sarasota, Florida, where he became that city’s first Black orthopaedic surgeon.

As Morgan was finishing his residency, a young James Hill, ’74 MD, ’79 GME, who had just completed medical school at Northwestern, started an internship in the department. By then, he had already experienced his share of discrimination in medical school — not being able to complete an OB-GYN rotation with his medical school classmates, for example.

“I was the only one in my class to rotate at Cook County Hospital, while the others rotated at Passavant; I guess some of the Passavant patients didn’t like the idea of me watching them,” he said.

He continued on in the department as a resident, then joined the faculty in 1980, and stayed at Northwestern for more than 40 years and counting. He is now a professor of Orthopaedic Surgery.

During the course of his career, Hill has provided care for the National Football League and Olympic athletes as well as underserved communities in Ethiopia. He was on the board of trustees at Talladega College, Alabama’s oldest historically Black liberal arts college, and is a founding member of the J. Robert Gladden Orthopaedic Society, an organization dedicated to increasing diversity in orthopaedic surgery. In 2020, he received the Diversity Award from the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons.

‘The Torch Passing Is Essential’

In the 1980s, while they were both at Northwestern, Hill and Morgan met the talented Mackel, who was doing a summer internship at a hospital in nearby Gary, Indiana. Later, when Mackel applied for his residency at Northwestern, “We knew we wanted him,” Morgan said.

“They validated me to other faculty members,” Mackel said. “Having that kind of network has helped all of us, and it is why we are working so hard to continue to build that community now.”

Mackel is the author of several published articles and book chapters about orthopaedics. He has been in a private orthopaedic surgery practice since 1988 and is a clinical instructor at the Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine as well as division chief of Orthopaedics and the past president of medical staff at St. Vincent Charity Hospital Medical Center in Cleveland.

Decades into their careers, Morgan and Hill were also mentors for Linda Suleiman, MD, ’17 GME, who is now an assistant professor of Orthopaedic Surgery and assistant dean of Medical Education at Feinberg, as well as director of Diversity and Inclusion at McGaw Medical Center. She is making her mark not only on the future of medical education, but also as one of just six Black female surgeons in the country trained to perform joint replacements.

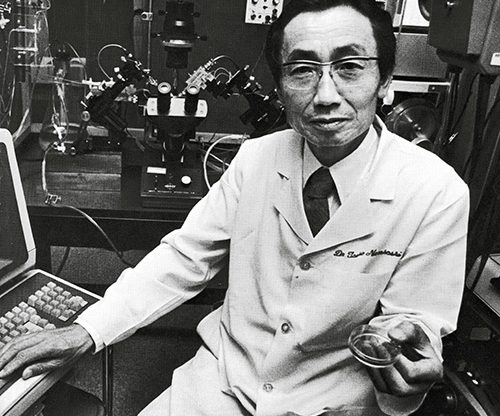

Clarence Woods, MD, holds a name tag from a past Feinberg reunion, showing his medical school graduation picture.

While it was a long road for Suleiman, she knew from the get-go that her predecessors had her back. In 2012, on the first day of her residency, she received a voicemail from Morgan wishing her good luck. A decade later, she still keeps this message saved on her iPhone, and she played it for everyone at the dinner — just before sharing a photo of herself and her own protégé, Muhammad Mutawakkil, MD, ’22 GME, seated next to her, who was recently hired by the department.

“He is like my little brother,” she said, pulling him in for a hug.

“I met Dr. Suleiman when I was doing a trauma rotation during a summer program at Northwestern, and she is one of the biggest reasons I wanted to come here for my residency,” Mutawakkil responded affectionately, adding that now that he has completed his training, he feels a sense of duty to pay it forward.

“The torch-passing is essential. Look, it’s been more than 50 years since Dr. Woods started his residency, and there have still only been 13 of us,” he said. “I have to do my part.”

‘I Guess I Do Have A Place Here’

Another colleague at the table was Erik King, MD, ’98 GME. Now interim division head of Orthopaedic Surgery and Sports Medicine at the Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago and associate professor of Orthopaedic Surgery at Feinberg, he, too, was no stranger to racism during his residency.

“When I was a resident, this was around 1996, I went to see a patient at my attending’s private clinic. When I came into the room, the patient told me he didn’t want to see me. I didn’t want to force myself on him, so I left and told my attending, Dr. Greg Palutsis, what happened. He sent his nurse in to explain that I was the resident and would see him first, and that Dr. Palutsis would follow. When I returned the second time, the man still refused to see me. The nurse communicated to us that the reason was because I was Black. So, Dr. Palutsis went into the room with the man’s coat, told him that if he wouldn’t see me, then he wouldn’t be seen at the clinic, and showed the man the door. The patient left, and that was the end. My attending lost a patient because he stood up for me. And I thought, ‘Oh, I guess I do have a place here.’”

King did, indeed, find a place at Northwestern. After serving as chief resident at Lurie Children’s (formerly Children’s Memorial Hospital), King was recruited, upon the completion of his fellowship in Pediatric Orthopaedic Surgery and Scoliosis at Texas Scottish Rite Hospital for Children, to return to Northwestern as faculty — and has been here ever since. He was the first Black full-time surgeon at Lurie Children’s.

Like his fellow alumni, King is proud of his Northwestern affiliation. Together, these pioneers aren’t just working to give their best to their patients. They’re also out to change the face of orthopaedic surgery — and of all medicine — to give more people of color a place in the profession. They all agree that it will take time, and it will take allies like those they found during their own early days at Northwestern. But they aren’t giving up.

“What we accomplished didn’t happen in a vacuum,” said Morgan.

“And there is still plenty of work to do.”